Our climate is becoming more unpredictable and we need options. We need the autonomy of knowing how to put solutions in place ourselves. Knowing how to defend ourselves. Knowing how to protect ourselves. Knowing how to take care of our families, neighbours and communities.

Liz Sherborne is director of NeckTek, a designer and restorer. She and her husband Alex introduced earthbag building to Vanuatu in 2013. They founded Vanuatu Earthbag Building; an eco-building group that links volunteers and schools to water-tank projects in the pacific.

This interview is the third of four interviews with volunteers involved in the building of an earthbag water tank at Lucky Stars Sanctuary, Bywong. Vanuatu Earthbag Building assisted in this project. They have provided free plans, support and the materials required to build water tanks for people in need in fire zones in NSW Australia, cyclone zones in Vanuatu and Pacifica.

Gaele Sobott: You have assisted people to build tanks in Vanuatu and have just completed two tanks in Australia. How did you reach the point where you decided to help people build earthbag water tanks?

Liz Sherborne: Well, both Alex, my husband, and I have been volunteering and giving to charity all our lives. We were doing that long before we met each other. Over the years, we became disillusioned with charities and the waste of resources on CEO wages and marketing costs. We thought that there must be a better way to fulfil our moral obligations to society, and we decided to do our own volunteer work.

GS: What does moral obligation mean for you?

LS: I believe very strongly that service to others is the rent we pay for our room here on earth. Muhammad Ali said that. Gandhi is reported to have said,” The difference between what we do and what we are capable of doing, would suffice to solve most of the world’s problems.” I think the idea is very old. We use the earth’s resources. We are part of a community. Those of us who find ourselves on the better end of that deal have an obligation to help those in need. One of the events that spurred us on was when our government cut the Australian aid budget to the Pacific. The idea that we weren’t going to help our neighbours but that we were going to pollute the air and accelerate climate change was not acceptable. We thought, well, we can’t physically go and make our politicians make the right decisions. We can’t force a politician to pay attention to climate justice or what’s happening to the poorest people in our world. But we can contribute to helping our neighbours survive. We began by researching a lot of family volunteer holidays and discovered that most of them have middlemen that take most of the money that is raised. The money doesn’t actually end up with the people who need it for projects. So, we thought, well it can’t be that difficult to go to a country that may want volunteer assistance, make friends, listen to what it is that they need and help them.

GS: How do you finance your volunteer operation?

LS: We started just using our personal savings. Over the years, friends and family have sponsored tank materials, a couple of businesses that we work with and the Corrilee foundation have paid for materials. We are not a charity and we don’t take donations but if someone wants to come along and help or pitch in on the costs on the concrete or the bagging, then we happily accept.

GS: How did you come to the decision to proceed with earthbag building?

LS: First, we travelled to Vanuatu. Once we started getting to know people and listening to their problems, it became evident that they wanted a roadside market. The women we met didn’t have a safe place where they could sell their yams and their woven mats and their local produce. So the focus became providing them with a safe place to sell their goods. We then researched different methods that would be suited to tropical climates. Port Vila is one of the most disaster-prone capital cities in the world. So any structure you build will be hit by a cyclone, volcanic eruption, earthquake or tsunami within several months of building it. So we had to look for something that would survive all of that and we discovered earthbag building.

GS: How did you develop the knowledge and skills to start building?

LS: We corresponded with people overseas who had done this type of building and we learned by doing it. We just did it. The first tank was an experiment to see if it worked and it did.

GS: What were the problems you encountered? What were the successes?

LS: The problems in Vanuatu weren’t with the building process. The problems were more about negotiating land leases, the right to use land. Negotiating the rights of women to participate in the project and the ownership of the building. Project money disappearing. The problems were more culture-based than engineering problems. One of the more surprising successes was that a tank seemed to result in more girls going to school because they didn’t have to fetch water.

GS: Would you mind explaining how the idea for the project came from the community?

LS: One question I get asked by missionaries and charities is, how do you know you are helping the right people? I always find that a funny question, who are the right people? I see charities over there providing plastic water tanks to communities. They don’t follow up with what happens afterwards. They don’t train members of the community to maintain the tank. They don’t have friends in the community. They just deliver the tank, bring in a water truck, fill up the tank then leave. Sometimes the tank ends up rolled away to someone else’s house and a lock put on it so the community can’t use it. Other tanks are built attached to churches and only the church members who pay their tithe can use it. They are not really community assets. We build a water tank with any woman who asks for one and has organised enough helpers. So far, they have all maintained them really well.

We were lucky to meet a builder from Tanna called Philemon, who was essential to the project. The design of the tank needed to be appropriate to the island. Philemon’s input was imperative for that. We also paid a woman called Rachel, who went out to all the islands and started building tanks. There was no way we could have introduced the tanks to custom islands and remote islands without Rachel. We work with the local people, teach them how to build their own tanks and leave them with enough material to build one for themselves.

GS: How long have you been building the tanks?

LS: We built the women’s roundhouse in March 2013. The first water tank was built in January 2014. Since then we’ve seen more than 60 water tanks built. Some by Rachel, some by the Save The Children volunteers Rachel trained, some by St Augustine’s school, some by the Laurien Novalis Steiner school. We organised building holidays for some families who built tanks and a significant number were built by our friends and us.

GS: What would you like to happen in the future with the earthbag-building initiatives?

LS: I would love for this to be adopted in developing communities, especially coastal Pacific communities. At the moment versions of our tanks are being built in 8 countries on three continents. I just send the plans to anyone who asks.

I never thought we would need to build them in Australia but I found the bushfires towards the end of 2019 and early this year completely paralysing. The very air we were breathing was people’s homes burning, their farms, our forests and wildlife, burnt koalas. It was horrifying. We were breathing that air in Sydney. Alex and I were talking about it and we realised that the one thing we had to offer was the building of fireproof water tanks. We can teach people how to build their own earthbag structures in the fire zones. Then Helen Schloss contacted us about building a tank for the Lucky Stars Sanctuary. We thought, well building a tank for an animal sanctuary is different for us. We had been more focused on building structures that would benefit women, especially mothers. But Helen had organised people to do the work and they all wanted to learn. So we said, yes. COVID delayed the project but we finally got there. We were really amazed at how well run the Sanctuary was and the fantastic group of local people, and people from all over the place, who support the work that Kerrie Carroll does. We discovered that humans are definitely on the list of mammals that get sheltered there. It was the most fun we have had building in years.

In regards to the future, what I would really like to see happen is we vote for a government that acknowledges that climate change exists and addresses the emergency. Then we wouldn’t need to use our weekends doing this work. Failing that, I think it’s like barn-raising where you work in groups and help your neighbour. Building a water tank is really hard, dirty work but it can be fun. It takes four and a half days for a group of eight to ten people to finish a large fire reserve tank. The Lucky Star Sanctuary got a wonderful group of people together. But I don’t know if this form of tank building will take off in Australia.

The two tanks we built in NSW posed some problems. In Vanuatu, we worked with sand which was full of salt and the fill we used for our earthbag tubing was crushed coral. You’re not meant to put salt with concrete because it creates a chemical reaction. But it works in the tropics because the crystals from the chemical reaction inside the concrete seal off the capillaries and seal the tank. In Australia, we are not working that way. We can’t rely on the passage of time to seal our tanks and we can’t afford any seepage. We need to keep them drum tight. On the tank at Lucky Stars Sanctuary, we used road base and packed it so tight that it was holding water before we put the ferrocement on. We’ve adjusted the plans quite a bit to suit firefighting. After talking to the Rural Fire Service (RFS), we now fit a STORZ valve so they can connect their fire trucks and quickly refill their water. We had to re-engineer the entire tank design to suit the new conditions. We may refine the design even further according to the different contexts and situations we find when we build.

GS: I believe you are researching more about waterproofing the Australian tanks.

LS: Yes, we just found a fantastic local company that sells a flexible cement membrane that will keep the tank from seeping. This means we don’t have to rely on crystallisation.

GS: Would you describe briefly how the tanks are built.

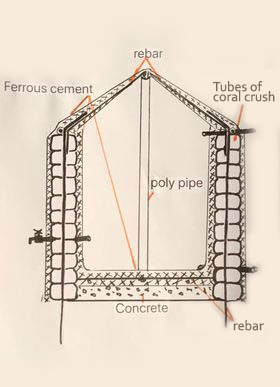

LS: We buy polypropylene tubing from Bundaberg Bag Co. It comes in long rolls. The last lot we cut into twelve-meter lengths. We fill that tubing with either earth which we then compact or with road base. Row by row as we build up and compact the fill down. We basically end up with a lot of rings on top of each other that look like flattened sausages. The tank at Lucky Stars Sanctuary required eight tons of road base just in the formwork. The entire tank needed eleven-and-a-half tons of material. We use ferrocement as the inner lining, then we put wire and cement down. We use the UNHCR recommendation of a two to one sand-to-cement mix on the inner lining. We work the concrete to reduce the capillaries and reduce leakage. On the outside of the tank, we again use a ferrocement coating. The idea is that you then basically have two structures which are helpful if you get a weather event like Cyclone Pam. If a coconut hits the structure at 260 kilometres an hour, it might smash the outer ferrocement wall. But the internal tank remains intact and this is why they survive, earthquakes, cyclones and fire. The inner tank is protected from natural disaster.

GS: Where has it been tested in a fire situation?

LS: Well, we had no idea about fire until several of our tanks were built on Ambae Island by Rachel. Soon after that, everyone was evacuated because of volcanic eruptions. Those tanks experienced eighteen months of volcanic hot ashfall. When the residents went back to the island, they found that all the fibreglass and plastic tanks had melted. Many houses had been turned to ash and the only tanks standing were the ferrocement tanks and our tanks. The ferrocement tanks were upright but not holding water anymore. Our tanks still worked because only the external wall had been touched.

We build a cone on the top to complete the tank. The reason we create a cone rather than a flat roof is to reduce the amoeba content in the water. You don’t want your water evaporating up to the tank ceiling and sitting there getting mouldy. By building the cone-shaped roof on the tank, it means the droplets run back into the water rather than stick to the roof and breeding bugs. In the tropics we line it with cement, here we now use an extra layer of flexible cement membrane. After that, we cement render the entire outside of the tank, for added strength and so there is no UV damage to the bagging. Sometimes we raise tanks up by building them on a base. In the case of the Lucky Stars Sanctuary, the ground was hard. So we compressed road base for the tank to sit on. I don’t think we’ve ever built two tanks the same way. When we completed the last tank, we asked someone from the RFS to check it out for us.

GS: How much does it cost to build one of the tanks?

LS: If you buy at suburban retail prices and have all your materials delivered. If you use compressed road base and if you use all the fancy fittings we used on the latest tank it costs $1610.00. That’s for a W12000 litre tank. In the islands, we can build one for less than $600

GS: How much would a plastic or ferrocement tank cost?

LS: A plastic tank would cost over $2000.00 and I think a ferrocement tank delivered is between around $10000.00 to $15000.00.

GS: What would you like to say to finish up this interview?

LS: This form of building suits extreme climates with low labour costs or willing volunteers. It is very adaptable. We started this project in Australia not because we thought that this was the best water tank available but because it was the only fireproof one that could be built by an unskilled team. It was all we could offer in the face of such tragedy. You can literally use the burned land to stuff the bags and rebuild. The tank project allows people on the fire front to talk with each other about their losses and exchange information and innovative ideas. Coming together and working as a group of volunteers on building a tank can serve as a kind of therapy. It may also help people to feel more in control of their future. Some of the promised assistance has been non-existent. It is possible to organise and support each other and also support the RFS by providing water reserves. People realise they can actually build a bunker, a water tank, a safe shelter for their animals. You can start small. Build it up bit by bit. There’s no deadline. You can take all the time you need.

On the build at Lucky Stars Sanctuary, we met a guy who is using scoria as his fill, which is like pumice, to build a safe house for his bees and protect them from the next fire. You can’t really put your bees in the back of the car with your kids and your dog when you are evacuating. He has built this fantastic beehive-like structure using earthbag building techniques.

Our climate is becoming more unpredictable and we need options. We need the autonomy of knowing how to put solutions in place ourselves. Knowing how to defend ourselves. Knowing how to protect ourselves. Knowing how to take care of our families, neighbours and communities. When people come together on these tanks projects, it has the potential to provide an antidote to feeling helpless and hopeless about the overwhelming devastation we went through with the last fires.

Interview conducted with Liz Sherborne at Lucky Star Sanctuary by Gaele Sobott, 11 October 2020.

Links:

Interview 1 in the series: Kerrie Carroll

Interview 2 in the series: Helen Schloss