Amanda King and Fabio Cavadini have been collaborating since 1987 as a co-producer/co-director team, making documentaries in a non-observational style combining interviews, archival and contemporary footage. They have worked together for almost 30 years tackling stories based in Australia and the region, about the environment, Indigenous rights and the arts.

Amanda King and Fabio Cavadini have been collaborating since 1987 as a co-producer/co-director team, making documentaries in a non-observational style combining interviews, archival and contemporary footage. They have worked together for almost 30 years tackling stories based in Australia and the region, about the environment, Indigenous rights and the arts.

Their latest films include, Time to Draw the Line (Frontyard Films 2017), A Thousand Different Angles (Frontyard Films 2010), Starting From Zero (Frontyard Films, 2002) and An Evergreen Island (Frontyard Films, 2000).

Gaele Sobott: We are going to talk about your new film, Time to Draw the Line, which focuses on the story of the maritime boundary dispute between Australia and Timor-Leste over an area rich in oil and gas reserves in the Timor Sea.

But first, I would like ask you to speak about what led you to become film makers, and describe how your interest in East Timor developed.

Fabio Cavadini: You want the long version or the short one?

GS: The long version.

FC: I wasn’t a film maker when I came to Australia from Northern Italy, near Milan, in 1969. I grew up mainly in Switzerland. My father died when I was three. My mother was a waitress. In those days, waitresses had to live on tips. They didn’t get a wage. My mother needed to travel to wherever the tourists were. So, during summer she was at the lakes or the seaside. In winter, she would work in the mountains. We were jostled around all over the place. Staying with my grandparents in Italy was the best time I ever had. The worst time was when we were locked up in homes because she didn’t have any money. I was originally intending to go to New Zealand but my brother was already in Australia and he wrote to me encouraging me to go there. I was a dental technician, specialising in making chrome cobalt plates. They were very thin and at that time there were not many people in Australia who could make them. I came as an assisted immigrant. I didn’t speak any English but it wasn’t a problem. I worked straight away.

I didn’t know anything about Aboriginal people or that they even existed in Australia until 1972. My brother, Alessandro Cavadini, was making a documentary film about the Left in Australia but the Left in this country was scattered all over the place, the in-fights, the ego-maniacs. Aboriginal people were very strong and unified in fighting for their rights. So he ended up making the film Ningla a-Na, about the first tent embassy in Canberra. I got involved. I liked still photography and I was happy doing odd jobs here and there. Subsequently I met some Aboriginal people who were involved in Basically Black, Bob Maza, Aileen Corpus, Zac Martin, Bindy Williams and Gary Foley. They were playing at the Nimrod Theatre at the top of Williams Street and were about to go on tour. They wanted somebody to take photographs and help with the lights so I stopped my work as a dental technician and went with them on the bus for six months. It was very exciting.

GS: Where did you tour?

FC: We went to Townsville and Innisfail. There was a festival on at the time. We also went to Yarrabah Mission up near Cairns. On the way, we met other people. In Townsville, people knew about Ningla a-Na. They said, “We want to tell our story too. Why don’t you come up?”

When I got back to Sydney I spoke to my brother and his then partner, Caroline Strachan, who managed to raise some money to make a film on Palm Island. I was earning a good income as a dental technician but it didn’t mean anything to me anymore so I didn’t go back to the job. Instead, I went to Palm Island. We made the film, Protected, in 1976. I was taking the photographs and generally helping. I’d never made a film in my life, and hadn’t touched a film camera. In those days, video was far lower quality than it is now so we were using 16mm film.

It became obvious that the project was going to take longer than we had originally thought. We were doing workshops so that the Aboriginal people there understood what film was. Plus, they were the ones telling the story. The story belonged to them. They had the connections, a cousin, a nephew, sons, daughters. They were acting in the film, controlling a lot of the process. They were intrinsic to the story telling so it was going to take time. It’s always a collaboration.

GS: Can you talk a bit more about the importance of taking time when you are collaborating on creating a documentary?

FC: Whenever possible it’s important to allow people to fully participate in the project, in the creative process. Ultimately when you’re making a film, you are not making it by yourself. You make it with many other people who are bringing their private life, their lived experiences to the story so they should have a say. They should have a principal part in shaping the story. That takes time. Especially when you are working with people who may have no knowledge of what film making is. Sometimes in the film industry, film makers say, “Oh yeah, I’m making a film because such and such a film festival is coming up.” They want it ready by a certain deadline and rush everything. To me that doesn’t make any sense. You need to take time to make a film, especially documentaries. Sometimes they are quicker, sometimes they are slower depending on the location, the people you are dealing with. Things change because you’re dealing with real life. So, you must adapt.

GS: So, the project was going to take longer than originally planned.

FC: Yes, the cinematographer decided he couldn’t stay for the length of time necessary to do the project. It was difficult at that point to find somebody to replace him. I knew about lighting with my stills photography so he showed me how to use the camera. Then he left the camera with me and I shot my first film. I didn’t know how well I was shooting because we had to send the stock back to Sydney to be processed. The only reports we got from the lab were that there were no scratches, there was an image and it was in focus. We didn’t know anything else until we got back.

We made another film after that called, We Stop Here, because the people of Palm Island said, “Oh, you must go to Tully on the upper Murray river. The people there have a story to tell.” The Dyirbal Elders were directly connected to Palm Island. Their families were taken away from the land and put there. Palm Island was a penal colony, a jail. The government was putting people on there from Queensland and the Northern Territory.

That’s how I started making films.

GS: What do you think drew you to making documentaries on Aboriginal experiences?

FC: Possibly it was because of my upbringing. Living in homes like I did growing up, I learnt about injustice. In those circumstances you gain a perception of what society is really about, especially the way capitalism works. I’m not speaking from the point of view of a socialist or communist, in the sense that I have never belonged to any party. I’m more an anarchist. But I don’t like the way our society functions. I never liked it as a child, and I still don’t like it now. That is perhaps why I have a very strong interest in working with Aboriginal people to assist in telling their stories. When I came to this country I was given all sorts of information like don’t go into the sea because there are sharks, and be careful of spiders and snakes. Suddenly I saw another reality – the struggles of the Aboriginal people who own this land.

GS: When did you first become involved in making films about East Timor?

FC: I was part of the team that made, Buried Alive, the Story of East Timor, the first Australian film to examine the terrible death toll and the resistance of the Timorese people following the Indonesian invasion in 1975. I co-directed with Gil Scrine and Rob Hibberd. I filmed José Ramos Horta, following him around in Australia, Mozambique, New York. There were only the two of us travelling. I had my own equipment. You could do a lot with very little money. That’s the way I’ve always operated.

Mandy and I make documentaries on low budgets. It used to be more difficult when the only option was to shoot on film. Now with modern technology you can do the production at home on your laptop.

GS: What about you Mandy? How did you start your film-making career?

AMANDA KING: A slightly different story. I went to art school in Newcastle to do training to become an art teacher. That was from 1973 to 1977 and film was the new big thing in art school. Film courses weren’t even established then so we were taught by the local ABC camera person how to operate a Bolex but basically, we were working with video.

It was while I was a student that I had my first contact with the politics of East Timor. In 1975 when Indonesia invaded East Timor and when the Australian journalists were killed there were a lot of protests. Newcastle was a strong unionist centre. It has a strong Workers’ Club, and the Communist Party. There were a lot of meetings, demonstrations on the street and that sort of thing. The killing of the five journalists affected people. It came a lot more real to Australians when Australian citizens became victims of that invasion. I took part in the demonstrations against the Australian government’s inaction to take up the case or do anything about the invasion.

So, I didn’t go into teaching because of my interest in film. I ended up in Sydney and around 1985 Martha Ansara, who is a well-established film maker herself, was approached by José Ramos Horta to make a documentary about East Timor. He obviously realised the value of films to inform people and the story was not being told. She was a bit busy at the time so James Kesteven and myself took on the project as directors. The film was The Shadow Over East Timor. We worked with Denis Freney, the journalist, who did a hell of a lot of research. He was a Communist Party member, an activist, who had very good relations with the Timorese community in Australia. He was an excellent journalist and researcher and had a lot of knowledge about the geopolitical aspects of the East Timor situation, the subtexts of what was going on politically.

GS: What were the subtexts?

AK: Well, the American and British involvement, the armaments industry, who were supplying the Indonesians with planes and armaments. Also, the background of what happened in the 1970s which included Gough Whitlam giving the nod from the Australian Government’s point of view. The Americans were well informed of the Indonesian army movements at the time and the invasion was okay by our government. This was one of the black marks against Whitlam. I’m a great admirer of a lot of things that he did but with Timor he had some sort of a rationalist attitude believing that small nations were not viable and East Timor was not going to be able to become a successful independent country.

We began work on The Shadow Over East Timor in 1985 and sent the finished version to SBS in the late ‘80s. We didn’t hear anything for a long time but then a producer at SBS, Barbara Mariotti, realised that actually this film was saying something that Australians probably would be interested in. There was a lot of Australian content in the story, Australia being such a near neighbour to East Timor. Then SBS came on board, in contrast to their response to our current film, and offered to purchase The Shadow Over East Timor. So, we said, “Why don’t we make it a proper television hour?” It was only about 38 minutes at that point. That would be adding another 20 minutes to the film and meant that we could contemporise it a bit. It allowed us to bring it up to date on the oil issue and interview some more Timorese people who could give eye-witness evidence of the level of oppression that was going on in a country. Timor was virtually blockaded from the world. Technically people could go there. Outsiders could visit but they tended not to because of the heavy vibe of intimidation. It was a neglected country with a strong military presence.

Fabio and I met because we were both concurrently working on documentaries about East Timor, and he came to watch our film. Then, because we got SBS interested in The Shadow Over East Timor and decided to expand the film, we decided to go to East Timor together to try to get new footage. That was the end of 1989. But unfortunately for us because everything had to be organised semi-clandestine in order to get in there and talk to people on the ground, it was quite an involved process. Unbeknown to us, José Ramos Horta had organised for Robert Domm to go in. So the week before we arrived in Timor, Robert had walked up into the mountains and got an interview with Xanana Gusmao. We had no idea.

FC: The ABC broadcast the interview with Xanana on the actual day we arrived in Timor so Indonesian intelligence were on high alert. We arrived by plane. There were four white people on the plane, Mandy and myself and another couple. The atmosphere was really tense. The country was occupied by Indonesia and a lot of killing was going on. Everyone was mistrusting everyone else. They didn’t know who was spying. A lot of people were forced to spy because their family was threatened and so on. We had the Indonesian secret service attached to us wherever we went. They were following us constantly.

AK: It was overt.

FC: They questioned us. What is your job? What are you really doing here? I had put my occupation down as house painter and Mandy had said she was a teacher. We said we were tourists, there on holiday. But they were obviously suspicious of us because we had a video camera and tourists were not going to Timor at that time. We had contacts and we had to wait there for them to come. We had to be patient. It was pretty full-on. Some students came to see us at night, talking to us, the next thing we heard a noise and the students disappeared.

AK: There was a curfew in Dili so truckloads of soldiers were patrolling the streets.

FC: With no lights on. Trucks full of Indonesian soldiers. It was quite freaky. It was a disastrous trip.

AK: We did get interviews with students in Jakarta, and we did finish the film.

FC: We had that footage with us in Timor because we had been to Jakarta first. We were in Timor for about three or four weeks so we thought in case the Indonesians search us we should do something about the footage. We opened the cassettes and cut the tape, rolled it on pencils and hid the pencils in various places. They didn’t search us in the end. When we got back to Australia we spliced it back together.

AK: The footage survived. That film was released on SBS months before the Dili massacre. It touched a nerve and got quite a lot of publicity. Buried Alive had been screened by the ABC the year before.

Time to Draw the Line cinema-on-Demand poster & DVD cover. Original artwork Tony Amaral

GS: What led you to make your latest film on Timor-Leste, Time to Draw the Line?

AK: We made another film, Starting from Zero. It came out in 2001. The story follows three people who had come to Australia as refugees in 1975 and went back to Timor during its transition into an independent country. We maintained connections with them. Most people in Australia think, well, East Timor is independent now. Everything’s ok. They are getting some money from the oil. They should just move forward and do the best they can. But it became clear to us through our continuing friendships with Timorese people that things were not quite right and Australia figured significantly in that story. It became much clearer to us through the process of making Starting from Zero that Australia is playing a big role in denying the Timorese their full sovereignty. It’s about the resources in the Timor Sea. This is the last hurdle that needs to be jumped. The Timorese are fighting for full sovereignty, full rights to their territory. They are fighting to define the borders, the maritime boundaries, as it’s vital to them achieving full sovereignty. We have been making these films over decades now in support of exactly this.

FC: We made films in Bougainville and Papua New Guinea that centre on the modus operandi of Australia in the region. It doesn’t matter which party is in power, Liberal or Labor. It’s the same. Australia is exploiting these countries. No respect. You see that in Timor, in Bougainville, in Papua New Guinea with the mining companies. BHP went to Papua New Guinea, opened a mine. Australia was happy. The company destroyed 700 kilometres of river. One of the biggest rivers in Papua New Guinea totally destroyed. Then they took off. That is what our film, Colour Change, is about.

AK: We made An Evergreen Island about the people of Bougainville under military blockade. In 1989 the land owners asked the company running the copper mine for proper compensation for damage to their land. These mines are massive and the impact on the local environment, in this case, 17 years of toxic waste and pollution, was horrific. People from many of the communities were living from the produce of the land. They were and still are catastrophically affected by the destruction. They had been negotiating with the company to get decent compensation and the company just said, No. We pay our royalties to the national government. End of story.

As the customary owners of the land, women were instrumental in setting up the Landowners’ Association, from which a core group of members formed the Bougainville Revolutionary Army and trained up in guerrilla tactics to defend their land. A number of local people were employed by the mine and they knew how it operated. They identified one weak point. It relied totally on one power source. Generators that were down at sea level. Power cables brought the power up the mountain to the mine. So, the landowners led by Francis Ona exploded a couple of power pylons and the mine was no longer functional. We heard that news report at the time. The brilliance of the tactic struck us but obviously, the consequences were severe bringing mayhem to the people because the army and police were brought in and almost a ten-year total sea and land blockade occurred on that island. We went there in 1997, towards the end of that blockade. We were attempting to do a character profile on Sam Kauona, general of the Bougainville Revolutionary Army. He’d been trained by the Australian army. He was working at the ammunitions depot when there was a big increase in the ammunitions order. He was thinking, why? Why are we suddenly needing all these ammunitions? He put two and two together. There was trouble in Bougainville and that was where the extra ammunitions were destined. The ammunitions that he was going to be handing out were to be used against his own people. So, he effectively deserted. It was a powerful story. We spent quite a lot of time with him and his wife, Josie, in Bougainville. On the way in, we hung out waiting to be picked up by the BRA, then travelled across the ocean in a banana boat looking out for the patrol boats and helicopters. We crossed the blockade. Once again this was an Australian story because the Australian government had given the PNG government patrol boats and access to helicopters.

FC: And pilots.

AK: Yes, and they were enforcing this blockade.

FC: The PNG army was shooting people. When they captured some of the BRA they tortured them but also some were taken out to sea in the helicopters and dumped. These events were recorded. The Australian government was supplying armaments, equipment and pilots.

AK: There were no Australian soldiers on the ground but there were Australian and New Zealand pilots involved in flying the helicopters.

GS: In relation to your new film, Time to Draw the Line, you were saying it was through your continued contact with Timorese people you met in the 80s, that you became aware that the exploitation of oil resources in the Timor Sea. And this was central to the ongoing Timorese struggle for full sovereignty. Would you like to talk more about that?

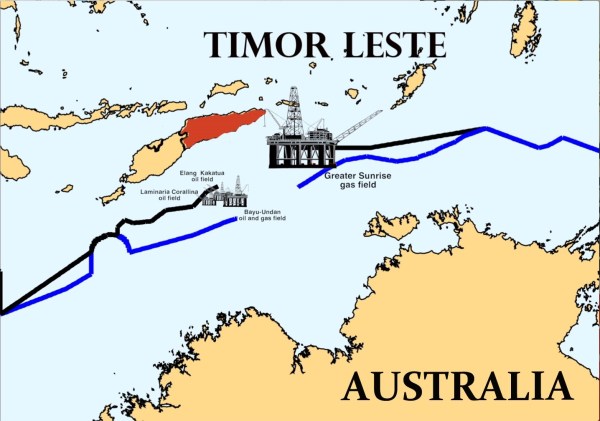

AK: Yes, one of the most astounding things is that Australia has completed negotiations with every other neighbouring country for just over 98% of its whole maritime boundary. Large amounts of that boundary have been negotiated according to the principle of the median line under international law where both countries conform to a median line equidistant from their shores. The boundary between Timor-Leste and Australia is the 1.8% of Australia’s maritime boundary that remains unnegotiated. There is no maritime boundary here. Two months before East Timor’s independence, Australia withdrew from maritime boundary dispute resolution mechanisms of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Many commentators conclude it was a move to avoid involving the international umpire in any future discussions about boundaries.

Diagram showing the 1.8% of Australia’s maritime boundary that remains undefined – the boundary between Timor-Leste and Australia.

We know how powerful the argument of borders is, and how politicians like to refer to borders in relation to refugees who come by boat to this country. The poignant aspect of this story is Australia’s politicians are infatuated with borders but they do not have that same infatuation in relation to the 1.8% of our maritime border that relates to Timor-Leste. Why is that? Every Australian should be asking themselves, why is that? There is a huge anomaly there. What is the story?

FC: As Steve Bracks says in the film, we can’t criticise China’s stance on the South China Sea when we are acting this way in the Timor Sea. It’s hypocritical.

AK: We are a wealthy country and our neighbours are not. Particularly Timor-Leste. Maternal mortality is 83 times higher in East Timor than in Australia. Malaria and tuberculosis are widespread. Education is desperately needed for future development. The oil and gas fields are on Timor-Leste’s side of the median line. The country desperately needs this revenue.

FC: Well, I just want to add that we are a wealthy country for some people, not for everybody.

AK: That’s true.

GS: Tell me more about the process involved in making Time to Draw the Line. How did you begin?

FC: We formulated the idea with Janelle Saffin and Ines Almeida who came on board as associate producers. We’ve known them for many years. Janelle served in both the Federal and State parliaments as a member of the Labor Party. She’s a lawyer and was an official observer for the International Commission of Jurists at the 1999 independence referendum in East Timor. Ines was one of the characters in our film, Starting from Zero, about the Timorese people going back to their country. She has been at the forefront of the struggle for Timor-Leste independence and now to secure their sovereignty with the marking of maritime boundaries. We decided to concentrate on the Australian angle of the story. It is a message for Australian people from Australian people. We only have a few Timorese people coming into the story.

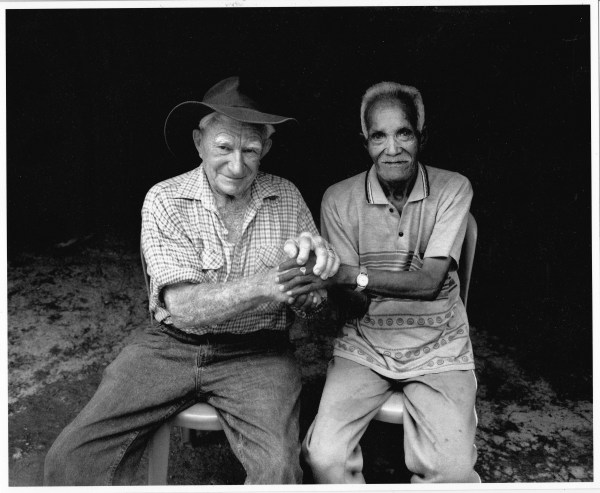

AK: It was an organic process. Obviously, we had an outline. We contacted a lot of people who have been more deeply involved in the issue of full sovereignty and defining the borders, and what’s going on with the oil. We started filming in the street in Melbourne to get a sense of how well informed Australians were. So then it moved organically from there, talking to a very deliberate cross-section of people in terms of their political backgrounds. Most of them feel very passionately about the issue. That is what has given the film a lot of energy and life. As well as those perspectives on the current situation, we did some historical storytelling. From our previous films, we know that the 1943 involvement of Timor in the Second World War is such an important element in Timor-Leste – Australia relations. Australian soldiers in the 2/2nd Australian independent company went to Portuguese Timor, as it was known then, a neutral country, and many of those men felt very passionately about the support they had been given by the Timorese people at the time. The Australian mission was unsuccessful and they withdrew but our soldiers saw with their own eyes the beginning of the Japanese retaliation against the young Timorese people who had been supporting and protecting them. As the Australian soldiers were rescued by boat, Japanese soldiers were coming down the hill and killing those young people. The veterans have maintained a campaign for over 50 years to get redress because the Timorese were promised, leaflets were dropped, saying, we will never forget you. Australia showed no signs of acknowledgement or generosity towards the country after the war. Now that Timor-Leste is an independent country, it has been able to reach out to the Returned Services League in Australia. The Timorese are building very solid connections with the veterans. That’s been going on for a ten-year period. There are not many veterans alive now. It’s a very significant part of the historical aspect of the story about the connection between the two countries. Some of those veterans have spoken out so strongly, and have been involved for a long time, particularly since the 1975 invasion.

Australian, Paddy Kenneally, WWII veteran, Sparrow Force, Timor campaign with Timorese veteran, Rufino Alves Coreia

FC: Paddy Kenneally was one of those veterans. He was a character in Mandy’s earlier film in the 1980s. The continuity is there. People involved in this kind of struggle are very committed. They don’t change. They firmly and staunchly keep fighting for what they believe and eventually they bring about change. There are many people like this in the film from varied political and religious backgrounds.

GS: You speak of the World War Two veterans and their support for full sovereignty where else does or will support come from within Australian society?

FC: It has to come from the people in the streets. It’s not going to come from the politicians. They play too many games. They always have and they always will. When the time finally came for the Timorese people to vote for their independence, we were filming Timorese in Australia and Mandy was there filming just before, the killing had already started, we knew, everybody knew that there was going to be a massacre if the Timorese people voted yes. But our government didn’t move to protect the people. Following the vote for independence in 1999 there were huge demonstrations in Australian cities. Thousands and thousands of people marched through the street. The government was forced to send troops but it was too bloody late.

The problem with our media is that the reporting centers on sensationalism. Something sensational happens and it goes on the news. It comes and it goes. There is no analysis, no depth to the reporting, it doesn’t continue over time. It’s as if these things happen with no historical or political context. That is another reason we made this film because it is a way of letting Australia people know what is going on. The Timor story is continuing and there is a dark side. The Australian people have the right to know. When we finished the film, we approached SBS, they weren’t interested. We went to the ABC. Compass was interested but they wanted us to cut it to half an hour and take out the references to the oil. This is the ABC mind you, forget about the commercial channels.

AK: To give the ABC due credit, they have done some excellent Four Corners stories on this issue.

So, not only do you have the Second World War veterans who are very passionate about Timor-Leste but you also have the 1999 INTERFET peacekeeping veterans who are passionate about the country. They made connections and friendship during their time there. They have on-the-ground knowledge of life there.

GS: Why are they speaking out? Do they see a disconnect with their peace keeping activities?

AK: Well, yes. The exposés of Australian government behaviour regarding East Timor made them question Australia’s role in Timor. They were peacekeepers. Most of them believed they were on a positive mission and the time they spent in Timor had a lifetime effect on them. They feel that there is unfairness and injustice that has occurred on Australia’s part. They feel betrayed on the oil issue and speak up very strongly in the film about the need for a median line boundary with Timor-Leste. In the early 2000s when the Timorese were negotiating to try to sort out what had been happening in the Timor Sea with the deals between Indonesia and Australia, they negotiated with John Howard and Alexander Downer, they managed to get what could be perceived as a reasonable percentage of the royalties and signed a treaty in 2002. But then after the discovery of the huge oil and gas field, ‘Greater Sunrise’, valued at 40 billion dollars, negotiations started again in 2004. Even though there is a strong case that these resources fall within Timor-Leste’s sovereign territory, the Timorese got tied up in knots and signed the 2006 treaty (CMATS). Part of that treaty locked them into not having any maritime boundary discussions with Australia for 50 years. Even such a huge oil and gas field as Greater Sunrise would be depleted within 50 years. One aspect of the negotiation is that it must be done in good faith. So, when in 2013, it was alleged by a whistle blower that the Australian government had employed people to pose as renovators of the government palace and install listening devices so they could hear what the Timorese were going to pitch for the Treaty, there was clear evidence that good faith was well and truly out the window. There’s no good faith if spying allegations are proven when you are in the middle of a negotiation.

GS: Australia is negotiating boundaries in relation to the oil and gas fields but who is extracting the resources from these fields?

AK: Woodside Petroleum has teamed up in a joint venture with Conoco Phillips and Shell. The Australian government granted Woodside leases over the Sunrise and Troubadour gas fields in the Timor Sea in the early 1970s. Australia has always claimed that its boundary was 150 kilometres off the Timorese coast because of the continental shelf. This is based on the reasoning used by President Truman in 1945 when he extended United States control to all the natural resources of its continental shelf. These laws were superseded in the 1980s by the UN and UNCLOS ruling which created the new international law of median line or equidistant boundaries. Australia is out of step with international law and as I said earlier, in 2002 just before Timor-Leste finally achieved its independence, the then Foreign Minister of Australia, Alexander Downer pulled Australia out of the compulsory jurisdiction of international courts and tribunals in relation to maritime boundary matters. Timor-Leste had been unable to call on an independent umpire to decide the border. But as Timor-Leste, has claimed the treaty was invalid, given Australian intelligence operations in 2004, and taken Australia to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, they are now in Compulsory Conciliation hearings for the next 9 months. It is a result of these hearings that the recent 2006 CMATS treaty will be torn up.

FC: I just want to add that Downer was Foreign Minister when the INTERFET peace keepers went to Timor. When he left government, he became a consultant for Woodside Petroleum. That would make anyone question Australia’s role.

GS: Do you think people demonstrating in the street in Australian cities would be enough to create change in relation to Timor-Leste achieving its full sovereignty?

AK: There should be layers of activity. Public awareness does play a very significant role and influences the way politicians behave. The Labor Party is now saying it will certainly enter negotiations to discuss the boundary, which the current government said it wouldn’t do. We have yet to see what this recent news of the abandonment of the 2006 treaty, is going to mean. Is Australia going to step away from its claim to the continental shelf?

FC: Time to Draw the Line shows Australian people from all walks of life. Timor strikes a chord in the Australian population. I grew up with the Catholic religion and it goes very deep no matter how hard I try to wipe it from my brain. One character in the film, Sister Susan Connelly, tells the story of Jesus saying to Peter, “Before the rooster crows, you will disown me three times.” She feels Australia disowned Timor three times. The first time was during the Second World War, the second time was the invasion and 24-year occupation of Timor by Indonesia, and the third time is in relation to the oil. Australia has denied Timor access to these resources. We have been doing this for a long time and we are still doing it. That includes the business and industry that is created around the oil. You can see how Darwin has benefited since the exploitation of the oil fields in the Timor Sea. Billions and billions of dollars has just been ripped off. If they sought compensation for all that money, they wouldn’t even need to extract the oil and gas.

Radford College students from Canberra with Timorese school children

AK: The Timorese set up a sovereign wealth fund. Something that this country has not done. Our population has allowed the exploitation of our mineral resources with no thought what so ever to the rights of future generations. It’s mind boggling how irresponsible our politicians have been in this regard. The Timorese have done a brilliant job in this regard. Every country with large natural resources should be doing as they have done. Australia doesn’t. It highlights the weird hypocrisy going on regarding the Timor Sea. A few hundred kilometres south-west of the Timor Sea in the Indian Ocean we have Chevron and other multi-national companies extracting oil and gas in our territorial waters and the Australian people will not see any tax from these companies for up to 30 years. We are trying to grab resources that are entitled to another people, and in our own territory we are letting multinationals cream it off through tax cuts.

GS: Do you think the Australian government serves the demands of multi-national companies before anything else?

AK: Yes, it appears that way. Those companies should not be assisted by national governments. They are making huge profits as it is.

FC: Then the politicians get high-paying jobs with those big companies when they leave government.

GS: You have not had much interest in the film from the main television stations. Do you see this as a form of censorship? How will you get the film to the public?

AK: Back in 1989, 1990, SBS could see that the Timor story was something Australians would be interested in. How many years later, 26 years later there is a totally different attitude. SBS does deal with risky subjects sometimes but when it involves our own national government, there seems to be a whole lot more sensitivity around it.

FC: Distribution is very limited. Television is a problem. Look at what’s happened to SBS. When we were first associated with SBS you’d go into their offices and all the departments were run by Wogs. I can say ‘Wog’ because I am one. It was enlightening to be there. Hearing people in positions of power speaking with accents, people with different perspectives on life. That’s what SBS was created for. Over the years these people disappeared from their jobs and were replaced by Anglo-Saxon people.

AK: SBS told us, “Oh, it will do well in film festivals.” They were positive about their negative view of the film.

FC: SBS did get behind some good films but when it comes to deeper, more analytical films, they say they are not interesting. They started doing all those cooking programs and now they’ve created a special channel dedicated to cooking programs. Don’t give the Australian public analysis, politics, history, give them cooking programs! There was some hope with ABC international but that was cut when the Liberals got into power.

AK: NITV does some excellent current affairs.

FC: NITV is changing too. You watch. That’s what goes on in this country.

AK: Other alternatives do sprout up. Social media provides another platform. One of the new ways of getting around the kind of censorship we are talking about, is on-demand type screenings. It’s potentially democratising approach to getting a film out to the public. You can show a film in any cinema in Australia.

We have put Time to Draw the Line on the Demand Film Australia site. People in the community can organise their own film screenings. It’s user friendly with an easy step-by-step format. This company helped distribute Chasing Asylum, Eva Orner’s film. It was shown all over Australia in single-event cinema screenings. We are hoping, not perhaps for that scale of success, but we know that Timor does touch a chord with many Australians and this is a story they will relate to. Al Jazeera English contacted us this morning. They will feature excerpts from the film in a current affairs program. This is a national, regional and international issue.

GS: How would you like Australian people to react to your film?

FC: Go to politicians and tell them what changes you would like to see happen. Protest the injustices, go out on the street if need be, and talk to other people. If you know something, talk to your friends, your neighbours, your work colleagues. Don’t just talk about the nice cooking program you saw last night. Tell others about Timor, about our role in Timor. People talking to each other about real issues is very powerful. Stop hiding behind life-style programs.

AK: Yes, we need to cut through the politicians. Australians are aware of what’s happening, they are concerned and they are watching to see how the politicians they voted for are going to respond. Politicians should not just be listening to the fossil fuel industry and prioritising the agendas of big companies over how ordinary Australians feel. Respect for our neighbours and their sovereignty is right up there.

GS: You have a history of collaboration and giving. You help people tell their stories, you help people who do not have the means to make films, you assist with advice, equipment, sharing skills. What advice would you like to give to young film makers?

FC: Don’t do what we did. No, I’m joking. The film industry is a strange animal. It encompasses a whole lot. There are people like us who work on political films but the majority of people may have different attitudes to film, to stardom, to money etc. We represent a very small slice of the film-industry cake but we are there. We were teaching film for over ten years, especially when there was not much money coming in. I always remember telling the students on the first day, “Don’t think that a documentary-film maker, especially one making social and political films, is going to make much money. You will be working bloody hard but you won’t be making much money.”

AK: There are all sorts of ways of telling stories. In Time to Draw the Line, Robert Connolly appears and speaks passionately about Timor. He’s a very successful feature film director, a tele-series director. There are all sorts of ways you can tell stories in this industry. But it is going to require persistence. If you feel passionate about using film to get stories out there that you don’t feel are getting the attention they deserve, stick with it. You will eventually succeed. The media is diversifying and changing. Often it is young people who are at the forefront working out creative ways to tell stories. They are always at the vanguard even though they probably don’t realise it. So, go for it!

Further Information:

Time to Draw the Line on-demand screenings

Time to Draw the Line Trailer

Time to Draw the Line Facebook

Frontyard Films website

Time to Draw the Line is distributed by Ronin Films

Amanda King and Fabio Cavadini were interviewed by Gaele Sobott in Sydney, 15 January 2017

Time to Draw the Line: an interview with Amanda King and Fabio Cavadini by Gaele Sobott is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.