Now is the time, with climate disaster upon us, to stop concentrating on fighting the boss and make the changes we want to see.

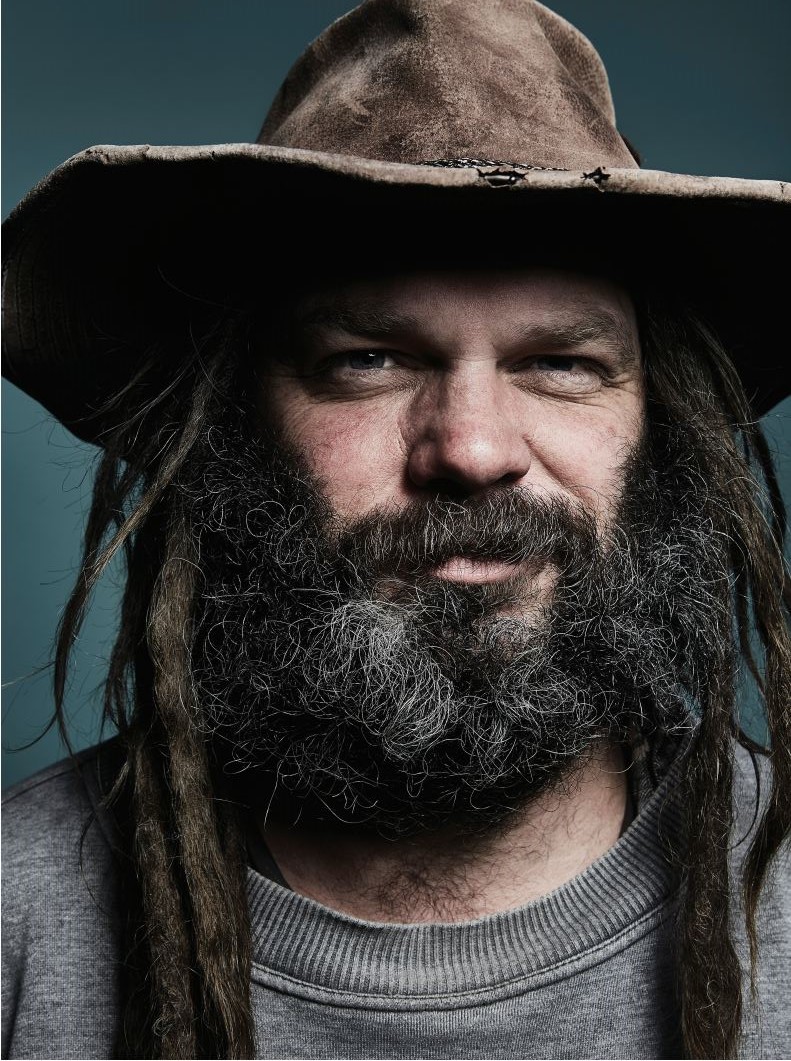

Scotty Foster is a solar powered, radio broadcasting, organic growing, co-operative creating, earth and people-protecting worker from Canberra, Australia. He currently earns a meagre living doing on and off-grid solar and general electrical work. Scotty is creating a co-operative commonwealth, through community groups, and on Community Radio 2XXFM98.3 with the ‘Behind the Lines’ show.

This interview is the fourth of four interviews with volunteers involved in the building of an earthbag water tank at Lucky Stars Sanctuary, Bywong. Vanuatu Earthbag Building assisted in this project. They have provided free plans, support and the materials required to build water tanks for people in need in fire zones in NSW Australia, cyclone zones in Vanuatu and Pacifica.

Gaele Sobott: How did you hear about this earthbag tank building project?

Scotty Foster: I heard through my dad. Someone told the Rural Fire Service that the project was happening. He’s with them, so he passed it on to me in case I was interested.

GS: Does the Rural Fire Service support this type of project?

SF: Yeah, I reckon they would love it. The more places that have tanks next to them specifically for fire protection, the easier their job is.

GS: Was the lack of water a problem in the last fires?

SF: It’s always been a problem around here, yeah.

GS: Why did you decide to get involved?

SF: Well, I can see that it is a simple construction technique that anybody can do. It’s not costly, and all you need is to raise some of your community to come and give a bit of a hand. It’s a very useful method of construction to know about. We’ve got a block out in the bush but we don’t want to be out there in fire season. Given the right conditions, it will go up in flames just like the last fires. We used to go there but now it’s too dangerous. In the previous ten years, fire danger conditions and the ferocity of fires have increased. We now have the new classification of ‘catastrophic’ fire danger. This earthbag technique would be perfect for building a fire shelter that meets the increased fire danger.

GS: How? Tell me more.

SF: The massive, thick walls would hold a lot of heat before transferring it through to the centre of the building. We need that mass in the walls and the sturdiness of the structure. It’s very strong and fireproof.

GS: Do you see other applications for this method of building?

SF: Yeah, it is now almost a year since the last fires began in NSW and there are still a lot of people down the south coast living in tents and caravans. Perhaps this method of building would be useful down there as well and help people to help themselves. If you look back 150 years, communities had building societies, where a bunch of people would get together and pool their resources. They’d then build one house after another after another until everybody had a home. It was a cheap and efficient way for the community to come together, and building codes weren’t such an issue back then.

GS: Are there currently barriers, laws, etc., that make it difficult for communities to go ahead and build as you are suggesting?

SF: Yes, there are many. The Extinction Rebellion mob have come up with a concept called a ‘dilemma action’ where a group of people take some form of action like blocking a road, or in this case building unapproved houses. If the government acts against the group, it will end up looking heavy-handed and idiotic. If they leave the group alone, then it sets a precedent. Building sturdy houses at this time for people who have been forced by fire and lack of government action to live in tents and caravans, is a great moment for that sort of action. I can’t see anything wrong with people getting together and just building their own good-quality houses. The need is huge. If you do it well enough, you can always come back with an engineer who says, ‘Yeah, that’s alright’.

GS: Some politicians are saying as far as climate emergency goes, we just have to adapt. What does adaption mean to you?

SF: Well if we keep putting carbon into the air, there is no adaption. We can’t cope with a climate that is three degrees hotter, let alone six degrees. I don’t know why they are doing this. There is no logic to it. They either deny that climate disasters are happening or they’re like Scott Morrison, who is part of a brand of Christianity which believes in the ‘rapture’, where the world ends and god takes all the true believers to heaven, leaving all the unbelievers to an eternity of hellfire. Of course their church is the only true one. There’s a possibility they believe that it’s time to end the world. Who knows what the motivations of these people are, but they do need to be stopped.

GS: What do you think the alternatives are?

SF: Adaption is one part of survival. Climate change is happening in a significant way, and we are locked into that. They talk about geoengineering. Most of those schemes are extremely risky and pretty crazy but there is one form of geoengineering that would be a really sound way forward. That is to convert the world’s agriculture into organic techniques that take the carbon out of the atmosphere and store it in the soil. We could take all of the world’s agriculture and use it to take carbon out of the atmosphere and to put that carbon back in the soil where it came from. That would go a long way. But we also need to stop damaging our habitat as a way of life.

GS: For this local area and the south coast, what do you think the immediate ways forward are?

SF: We need to change our building techniques for one thing. The way we keep building these crazy English houses here in Australia, particularly with the climate getting way out of control with fire season, bloody pyro cumulus nimbus clouds and firestorms. The earthbag design used to build this water tank protects against fire. Bring it on. Build houses, animal shelters, bunkers. You could build a house by bulldozing up four dam walls in a square, and put a roof on it, if you wanted to. Site it properly of course.

GS: What work do you do? What are you working on at the moment?

SF: I’m an electrician. I have been an organic farmer for many years. I’ve been a blockader and an activist. At the moment I’m building co-operatives to try and create a new economy that will make this crazy one, that is eating the earth and eating people, obsolete. Build an economy that is good for people and good for the planet.

GS: I had the impression that various regulatory hurdles and laws constrained co-operatives in Australia. Is that the case?

SF: It used to be that the co-operative laws were different in every state, which made it quite difficult to trade across state boundaries. That’s been fixed now. The Co-operatives National Law has reduced red tape and simplified financial reporting for smaller co-operatives. I mean you can use any form of governance as long as the registrar lets you do it.

GS: How are your co-ops going?

SF: So far, so good. We’re still in the set-up stage of the community-run farming co-op. We’ve got a renewable energy co-op which has put in one set of solar panels already. It’s called the Pre Power One Renewable Energy Co-operative. It’s designed to enable people who have a roof with a lot of sun shining on it but no money, access to solar energy. It also allows people in the area who would like to take their money out of fossil fuels and put it into something that is reasonably ethical, to do so.

GS: How does the investment bring a return?

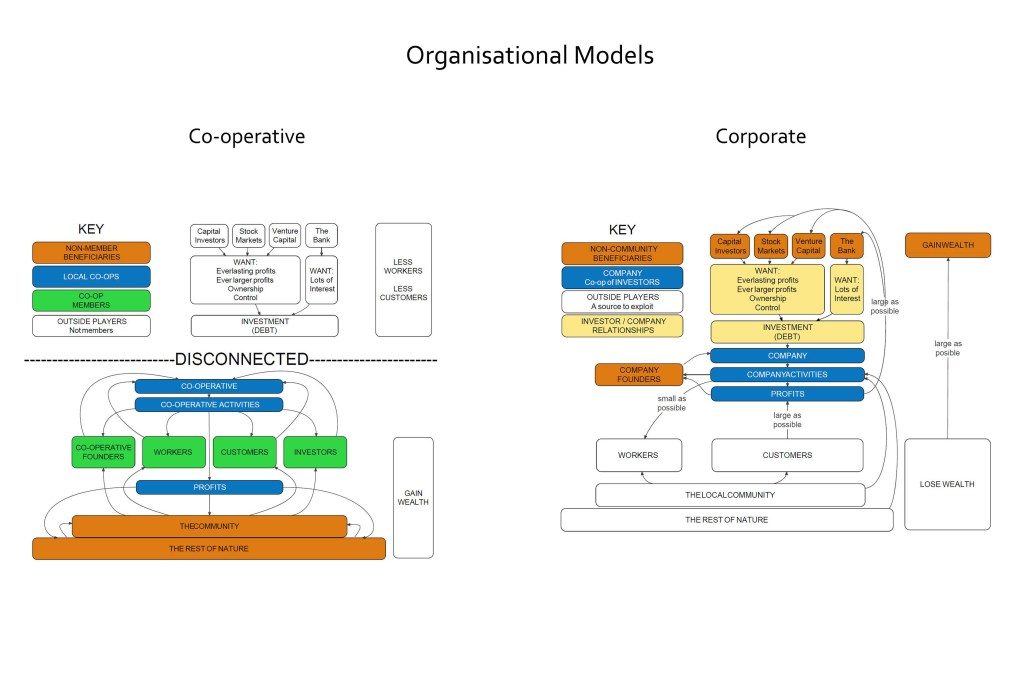

SF: So the way it works is that when you become a member of the co-operative, you get the right to do one of two things or both. If you have a roof that you would like the co-op to install solar equipment on, then you can put up your hand and ask for that. We will come around and make sure your house is suitable, for example, check that there is not a great big blue gum on the north side or something basic like that. If it’s good to go, then we will get a couple of quotes. Then we open up an investment opportunity for the other members who can choose to invest. We get the equipment installed for that member. That gets paid back to the investor when people pay their bills. A portion of that bill will go straight to the investor, and another portion will go to the co-op. The investor will double their money over about twenty years which is a lot better than super. It’s different from perpetual investment which is what most companies offer where if you invest once, you get the right to profits from that company forever. In our case, we prearrange precisely how much we will pay you back. We pay that amount, and the deal is done. You can invest again if you like. The beauty is that all the equipment winds up under the ownership of the people who are using it. That is a major problem in our society. Almost all the productive assets are owned by people who are either extremely rich or completely imaginary, i.e. a corporation. The purpose of corporate ownership is to extract as much wealth out of the community as possible.

GS: How do you maintain the solar units?

SF: There are two ways. You can either put a surcharge, a couple of cents on each payment. As hundreds of people are paying regular bills, we will have a pool of money that we can dip into. Or we can just raise another investment opportunity when the time arises that we need to buy something.

GS: How do you manage the co-operative?

SF: Management is critical. Currently in our society, management is almost always a very top-down, hierarchical, do-as-I-say model. We reckon that it is one of the leading causes of a lot of problems, certainly a lot of mental health problems. If we’re spending a large part of our time at a workplace where we have no control over our work situation, it’s going to affect us. We go through school under that model, and we leave school and face that model again in the workplace. Our families are that model because our parents were taught that model, and their parents too. So how do we do it differently? Luckily, people have been thinking about this for quite a while. We didn’t have to come up with an answer by ourselves. The intentional communities movement uses the sociocracy method of governance and decision making.

This is a system whereby the people who are involved in the community make the rules. The organisational units in the group are “circles” of people who have a defined way of meeting. A lot of the political and power problems that arise in groups these days are from a lack of structure in decision making. There is a lack of knowledge about how the organisation works. So, what happens is the members of the group have to make it up as they go along. Of course, the people who are very forceful and perhaps manipulative tend to rise to the top of that sort of organisation. Sociocracy and holacracy, which I’ll talk about later, are both flatter forms of organisation than the usual hierarchical forms of decision making we find in our society. Meetings are very structured and use a form of decision making called consent which is quite different from consensus. Consensus is where you all need to agree on something before it can go ahead. It can take a lot of negotiation. It is easily stalled by someone who is bent on getting their own way and doesn’t care about anybody else. It’s good for certain things. If people want to form the purpose of their organisation. Then it might be important to use consensus, so everybody is on the same page. Consent is slightly different. A proposal is put forward, and members ask themselves if it is good enough for now and if it is safe enough to try. It is an iterative process. If there are no objections, then the proposal can go ahead. If there is some doubt, the group can say, well let’s try it and come back to assess in a week or six months or a year.

GS: Are there cases where the iterative process should be applied regularly, anyway?

SF: Many of the newer organisational models that have come out of the tech revolution use iteration frequently. Lean methodology is an example of that type of management, but I’m not really up on that. I believe they use iteration a lot.

GS: I imagine it allows for more experimentation, but also it would assist with transparency and accountability.

SF: Absolutely. Our current organisational models do not make transparency and accountability a priority. Transparency and accountability are crucial to creating more humanised ways of organising where people are comfortable and in control.

GS: You said you are also starting up a community-owned farming co-operative. What management model are you applying to that group?

SF: We will be using holacracy which evolved from sociocracy. Sociocracy is an effective form of self-management in situations where there is a community of people living together, like housing co-operatives and other intentional communities. Holacracy is more structured and business-focused. It uses documentation and software, so it’s clear to everybody what the organisation is about. A new member can join the organisation, look up the website and know exactly what the group is about.

GS: Did you establish the purpose of the co-operatives before starting?

SF: We’ve tried both ways now. I came into the Pre power co-op as a bit of a ring-in. It was after the business people involved couldn’t get the concept of a co-op not being for-profit and needing to be controlled by the community. They graciously dipped their lids and bowed out, but then they needed to find someone else to be on the board, who was more aligned with the ideas we are now putting into practice. So, I wound up taking the position. We did have a few things to sort out like a purpose that really fits the bill. There are four of us involved and a couple of other people who come in and out, so it’s taking some time. There’s a lot of work to do in setting up a business.

GS: How do you protect yourselves from burn out?

SF: We make sure that if it is too much to do, we do it next week. We don’t pressure each other with timelines or anything but burn out is a real issue. Part of the model is to ensure that the structure will be easily replicable, so it will be easy for other co-ops to join in. A co-op is a business, and running a business is a pain in the arse and running a business as a volunteer after work is just ridiculous. It’s draining, especially if you’re working long hours. So the model we are working with envisages lots of local co-ops. Pre Power One is the first local co-op we’ve set up, and twenty per cent of the revenue from this co-op will go straight up to what we call Pre Power Central. That is a co-op that is owned by all of the local co-ops. Its sole job is to make life easy for the local co-ops. The central co-op will employ people with that twenty per cent of the revenue, whose job it is to assist with running a local co-op. They will be mentoring. There will be templates for co-op policies, insurance, arrangements with installers, basically all of the hard stuff. It makes it easier for a local co-op to set itself up. All that is left for the local co-ops to do is to hold a certain amount of board meetings per year, run the AGM and figure out what to do with the profits they make.

GS: Are the local co-ops volunteer-run? Are they able to pay themselves?

SF: The locals are basically volunteer run. We use twenty percent of a local co-op’s revenue to pay the central co-op to do most of the work. If a local decides that it needs to pay someone to do something the central coop is not doing, they can do that by agreement amongst the members. The effect would be that the extra wages bill would come out of the discounts received by the members of that particular local co-op.

GS: Earlier you asked, how we organise in a different way when all we know in our families, schools, businesses, government is top-down decision making with little transparency and less and less accountability. How do you think we can start organising differently?

SF: Well, sociocracy and holacracy is one aspect, but it is a huge task to change the existing systems and culture. Sociocracy has been successfully used in family situations before, but we are also going to have to start implementing these processes through education by opening up schools. How we fund those is going to be interesting.

GS: How do you see that happening on the ground say in this area?

SF: I see it as a later stage. The first stage we open co-ops like the renewable energy and the farming co-ops, where the people involved pay their bills. People already pay bills. We are encouraging them to stop paying bills to outside entities that make a profit from them. We want them to start paying bills to an organisation that is owned by them and controlled by them. A form of organisation where they get to decide how to spend any profit in a way which will benefit the community.

We are using a participatory budgeting scheme to distribute our profits. That’s where you have a pool of profits made by the organisation, and the members get to vote and decide how that money is spent. We will have a set of criteria for applicants to pass, and members can vote according to how much they want to give to who. For example, some of those profits could go to building and staffing a school, and some to say, elder care. These are services that are not suited to privatisation or to purely profit-making concerns.

GS: If as a community, you are taking on the responsibility of care and education of your members, does that mean you assume that the responsibility for these services does not lie at a state or national level, or do you envisage starting locally in order to make changes at state or federal government level?

SF: I guess the structure of responsibility that we want to build here is called subsidiarity. It means that decisions are made at the smallest possible level, so if your school can make a decision, that’s great, that’s where it should be made. Suppose there is a circle for cleaning within the sociocratic or holacratic structure of the school, and a decision needs to be made about cleaning. In that case, the cleaning circle should make the decision. If there is a kitchen circle, that is who should make decisions about the food. If you have a complaint about the food, go and see the kitchen circle. From there, you work outwards in a federal manner. You make formal arrangements with other entities that are doing the same thing, so with other schools. Anything that needs doing at a broader level like negotiating with the government or raising funds for particular projects can be done by all those schools agreeing to work together. This method or organising has been successful in northern Syria with democratic confederalism in the Kurdish areas. They spent seven years running a system that was working in exactly that way.

GS: I imagine it takes a fair bit of time to build the structures and culture required to run a system like that effectively.

SF: Major changes like this can really only happen where there is a power vacuum. For example, when Assad deployed all his troops to the south of the country to fight the Arab Spring. The Kurds, who have been fighting Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria, were well-armed and ready to build alternatives. They’ve been preparing for this for a very long time. Abdullah Öcalan has been around for a long time. He was one of the founders of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 1978. The party was not aligned with Russia when it started, and it didn’t take the official communist line as gospel. Because of this they were shunned by the communist world. They evolved towards democratic confederalism. In their guerrilla camps, they’d have a yarn around the campfire analysing how oppression arose historically and decided the first instance of oppression is probably the oppression of women by men. Gender equality is central to their organisational principles. The Kurds are known for their women’s army, which is also democratically run.

Sovereignty is held at the neighbourhood level. That is the ability to make and enforce rules. Within each neighbourhood, sub-communities are represented. The neighbourhood meetings work on a majority vote basis.

GS: How do you see this type of system dealing with exploitation?

SF: Okay, for example, there’s also a women’s council for each neighbourhood. So when decisions are to be made, the information goes out to a group of women in each sub-community. So, there are parallel structures at work in their social contracts.

GS: And wage exploitation?

SF: Well, the Kurdish example covers a very poor area. Historically, under Assad, it was mainly primary production, a lot of crops but no processing of the crops. It was all exported—the extraction of fossil fuels and that sort of thing. Everything gets taken out and shipped away. They have set up a whole system of co-operatives now to do that work. The local communities are federated. Say you’ve got a town with ten communities in it, they band together to organise water and electricity and all of that through co-ops they create in common.

GS: How do they meet their social needs?

SF: Through neighbourhood meetings, I suppose.

GS: Are you saying there is no need for wages?

SF: Oh, I see. I’m not sure. I haven’t managed to get a source about how the economic system works yet. But they have achieved an enormous amount, very inspiring, much longer-lasting and more peaceful than what the Spanish Civil War achieved. The Kurdish example illustrates to me that the federalist model with local sovereignty is entirely possible. It is a way to create a peaceful, sustainable society out of an absolutely turbulent situation.

GS: Here in Canberra, what do you do about the role of media which generally supports and enforces current power structures?

SF: We run a radio show, Behind the Lines on community radio 2XX and make a podcast called Align in the Sound. That is a three-way podcast between the New Economy Network of Australia (NENA), Behind the Lines and a group called Co-operatives, Commons and Communities Canberra (CoCanberra). So if there is something we want to learn, we do it in a public manner. We record it and leave it as a public record and information source that anybody can look up at any time. What a lot of people lack at this point are ideas. We don’t even know that alternative ways of organising and living exist. Who has heard of sociocracy or holacracy or what’s going on in northern Syria? Almost nobody.

GS: Tell me a bit about the organisations, CoCanberra and NENA you just mentioned.

SF: Every month CoCanberra and NENA Canberra region combine to hold a community information or study group night. For instance, we recently invited the National Health Co-op and a co-op from Sydney, called The Co-operative Life, who do aged-care and disability help. We sat the video conference TV on the couch at the food co-op, everyone else sat around it, and they talked about their models, with Q&A afterwards. One is a worker co-op, and the other is a consumer co-op. We were able to explore how they work and why, and what problems they face. We also do asset-based community development training. The idea here is that the community is an asset. The strengths and passions of the community need to be uncovered and used to build solutions to whatever problems that community is experiencing. When we discover or come up with new ideas, we run a workshop.

The New Economy Network of Australia is an Australia-wide networking organisation of people who are essentially trying to build a new economy. CoCanberra is about starting up co-ops and getting things implemented on the ground. The Pre Power and Community Owned Farming co-ops are projects that CoCanberra is deeply involved in. Radio Behind the Lines does long format interviews with anyone who is trying to make the world a better place.

Buckminster Fuller said, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” That’s what we are all doing.

Of course, we do have to fight the old system as well because it’s very quickly munching its way through the planet. The New Economy Network is a co-operative devoted to building a new economy. They’ve been around since 2016 when a conference was held in Sydney by the University of New South Wales law school and the Australian Earth Laws Alliance. At that point, there was no peak body in Australia, so they decided to form one. You can become a member of NENA. It’s got a really good website. They have geographic hubs, and they also have sectoral hubs like an education hub, a First Nations economics hub, housing, food, you name it. There’s a long list. You might live in a regional area, and you’ve got a passion or in-depth knowledge of renewable energy; you can hook up with people from around Australia who have similar values and skills. Behind the Lines is a community radio show that has been going for thirty-two years. I’ve been doing it for fifteen years. We work together with CoCanberra, and have recorded a lot of the New Economy Network conferences. If it’s appropriate to record the CoCanberra / NENA meetups, we will record them. We run editing training workshops over the web, building a team to polish up all that raw audio. Once we finally get them edited, We put them all up as podcasts.

GS: Do you work with unions?

SF: We’ve been trying to, but we haven’t had the numbers to form what they call a union co-op yet. There is interest in Canberra, and there’s a mob in Melbourne called the Earthworker Co-op. They bring together trade unionists, environmentalists, small business people and others in common cause. They began as a coalition of what was left of the Builders Labourers Federation after they got banned, alongside parts of the Green movement. Earthworker operates parallel to us trying to create a co-operative commonwealth on the ground. We are moving towards meeting our needs and capturing the profits rather than letting them go up to all the crazies who currently run the world.

GS: What are the main problems you see with trade unions in Australia.

SF: I think their principal problem is that they are stuck fighting the boss rather than working to make the boss obsolete. They are stuck in a perpetual fight, and that’s not good for culture, spirit or anything else. From being in the system, you become like that system no matter what principles and community support you start with.

GS: What is the main message you would like to pass on to people?

SF: We cannot afford to muck around with slow change any more. Now is the time, with climate disaster upon us, to stop concentrating on fighting the boss and make the changes we want to see by ourselves. We cannot wait for big capital to do it or for the government to do it. We have to do it ourselves; otherwise, it’s just not going to happen. We only have a few years, so we better figure out new ways of organising ourselves to displace the system that is currently ruining the world. Care for people, care for the earth. We can create economic systems that support socially just and ecologically sustainable communities. We can do it, but we have to act now to get it done in time.

Interview conducted with Scotty Foster by Gaele Sobott at Lucky Star Sanctuary, Bywong, 11 October 2020.

Links:

Interview 1 in the series: Kerrie Carroll

Interview 2 in the series: Helen Schloss

Great interview!! Scotty is a special person