Author: GaeleSobott

Time to Know Palestine:An Interview with Dina Turkeya

Dina Turkeya is a Palestinian dentist, author and translator. Her family is originally from Yaffa, but she was born and raised in Gaza. She has survived eight wars and aggressions, and still holds onto her dreams and ambitions. Dina’s love for her homeland inspired her to write her debut book, Time To Know Palestine (2024). She is interested in learning languages, writing, drawing and exploring different cultures.

Gaele Sobott: Please tell us a little about your family, including where they originate from and how their experiences have impacted your life.

Dina Turkeya: My great-grandfather was Turkish. He moved to Palestine in the early 1900s and married in Yaffa, where my grandfather was born. After the Nakba of 1948, my grandfather and his family were forcefully displaced to Gaza. He left everything they owned to start from scratch with the label ‘refugees’ on their identification cards. I still remember how my grandfather longed to return to Yaffa, their lovely house and the orange groves. He was waiting for the moment when his feet would touch his homeland after years of deprivation, but what happened was another Nakba. He was displaced from his house in Gaza to a tent in the south of Gaza in this ongoing war. His body couldn’t bear the inhuman conditions and the heartbreak of displacement again, and he died in the tent after years of suffering and yearning.

GS: Where/when were you born? Describe that place and tell us about your time growing up, including your experiences with siblings, cousins and school friends.

DT: I was born in December 2001 and lived my whole life in a very beautiful city called Al-Zahra. This coastal city is nestled in the heart of the Gaza Strip, boasting stunning natural beauty with lush trees, vibrant flowers, serene and spacious streets and kind locals. Growing up, I resided in our lovely house for about 22 years, which witnessed my earliest steps, first words, school journey and university studying nights. Every laugh, tear and whoop echoed through its walls. It was everything to me.

I had plenty of friends there and neighbours like a second family. I am the eldest of three siblings. We’d grown up in a family atmosphere full of love, involvement and support. My cousins were more than relatives. We gathered every Thursday, talked and shared our updates and stories, played cards and challenge games, ate delicious homemade food and desserts, watched movies and celebrated our special days. These weekly gatherings were cherished moments of respite from our bustling lives. I was fortunate to have wonderful friends I met through school, volunteer work, training programmes and even online international courses. True friends simplify life by offering guidance and support, celebrating victories and lightening the load on tough days.

GS: Apart from Arabic, what other languages do you speak? Where/how did you learn these languages?

DT: I speak English, Spanish and French. I’ve always been passionate about learning new languages. For me, language is not only a tool for communication but also a gateway to discover the world, learn new insights and open doors for new opportunities. My English proficiency was honed through school education and active participation in English clubs and programs. Similarly, I studied French for three years in primary school and continued for two years in secondary school, culminating in taking the DELF exam. Additionally, I dedicated three years to learning Spanish at Instituto Cervantes during my university years.

GS: Tell us what roles different languages play in your life and how different languages give or subtract from your view of the world.

DT: Arabic is my mother tongue; a rich, sophisticated and poetic language. The musicality and rhythm of Arabic, along with its diverse dialects adds to its charm and beauty. While I have studied many languages, none possess the deep meanings and elegant words found in Arabic.

Mastering languages has opened numerous opportunities for me, enhancing my skills in both personal and professional aspects. It helped me understand other cultures and perspectives, especially since living in Gaza has restricted my ability to travel and explore the world freely. Travelling is not a luxury when you reside in Gaza. It involves encountering various challenges along the way.

GS: Describe how the Zionist occupation of Palestine impacted your life from a young age. If it is not too much for you, can you comment on your experiences of the current genocide in Gaza?

DT: Throughout my 22 years in Gaza, I endured eight wars and aggressions, which left me grappling with feelings of instability and the lasting effects of violence and trauma. The constraints of the siege limiting our freedom of movement, the scarcity of electricity, and the obstacles to accessing education, healthcare, and economic opportunities all contributed to a persistent sense of hardship.

I still remember every detail of that unforgettable day on the 19th of October 2023, around 6:30 in the morning. A man’s loud cry of “Get out of your homes” jolted me awake in a panic, prompting me to rouse my family. We hastily left with only essential documents and some money. Seeking refuge at our aunt’s house down the street, we were startled by a deafening explosion, followed by another. The smoke was suffocating, my heart was about to stop from the intensity of the explosion. The shock and horror of losing our home hit hard as we realised it was our building that had been destroyed. I lost the place where I felt safe, warm, grateful and happy. I lost my sweet memories. I’m the kind of person who likes to save everything. I saved my childhood photos, the old coins, gifts and letters from my friends and family, my summaries, drawings and pieces of writing. I lost everything in the blink of an eye.

During the night, when the city was enveloped in darkness, we were startled by the sound of people running and screaming in the streets. We were informed that Israel was planning to bomb more than 25 towers in Al-Zahra city. Confused and frightened, we rushed out into the streets, unsure of where to go. Moments later, as the bombings commenced, the deafening explosion knocked us to the ground, prompting us to flee as far as we could.

More than 16,000 people found themselves on the streets. Surrounded by fire, the towers were under attack from the south, while nearby cities were being bombarded from the north. War boats approached from the west and tanks advanced from the east. Amidst this turmoil, babies were crying, the elderly were sitting in wheelchairs, women were screaming in terror and men attempted to calm down their families. I remember that even the dogs were running in panic at the sound of explosions, seeking refuge among the people. What happened is beyond the endurance of any human being and any creature with a heart and mind.

We spent 15 hours in horror; we were afraid, exhausted, cold, hungry and heartbroken. Not only the residents of Al-Zahra city witnessed this difficult night, but also other displaced people who had sought shelter in Al-Zahra after fleeing their houses. It was the hardest night of my life. I didn’t think that we would be alive the next day. I remember waiting for the sun to rise to warm us with its rays. The devastated city was shrouded in grey smoke, evoking a sombre atmosphere. We eventually evacuated to the south of Gaza, and tears welled in our eyes. Witnessing my once-vibrant neighbourhood reduced to rubble was heart-wrenching; a place that had once bloomed with flowers and love.

Even worse, Al Zahra city has lost all its landmarks and has been completely devastated by the continued bombing. Our city was built in 1998 to stop the expansion of Israel’s Netzarim settlement situated to the North. Netzarim was the last settlement to be evacuated and demolished by Israel when they withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005. Now, history repeats itself in an even more dreadful form. After forcibly displacing all the people in the area during the first weeks of this war of genocide, Israel created the Netzeim Corridor to divide the Gaza Strip into northern and southern zones. They did this by destroying everything in their way, including our beautiful city.

The bombs killed my cousin in cold blood. She was staying with her husband’s family. I didn’t get the chance to say goodbye to her before I left. She was dead under the rubble. It is heartbreaking not to be able to visit her grave, lay flowers or properly mourn her death. The harsh reality of her non-existence brings to mind the concept of annihilation. The pain is profound when someone you shared precious moments with — chatting, laughing, watching sunsets — is gone forever, and we have even been deprived of the solace of burial and mourning rituals.

Many of my friends and colleagues were killed as well. Each of them had dreams and worked hard to create a brighter future. They were simply trying to live, yet what they received was death. It is extremely hard for me to look at their pictures and realise that I will never see them again or hear their voices. I find myself recalling every conversation and every moment spent together. However, what brings me solace is the thought that they are in a better place, away from this evil and brutality. Their souls deserve peace and purification from this harsh world.

GS: Please talk about your tertiary education. What did you choose to study and why? Where did/do you study?

DT: I was studying dentistry at the University of Palestine. I have chosen this speciality because I feel that relieving a patient’s pain and giving him/her the confidence to smile is out of this world. I was in my final year when the war happened. I was so excited for my graduation after five years of hard work. It was the moment to reap the fruits of my efforts. I had many plans and dreams, envisioning everything as if painting a beautiful picture. War disrupted my plans, leaving me unable to complete my studies due to the destruction of my university. This unexpected turn of events forced me to put my dreams on hold, leaving me with a sense of loss and uncertainty. It’s truly heartbreaking to see how drastically our lives have changed, knowing that things will never be the same again.

GS: Tell us about your experience of leaving Gaza.

DT: Leaving Gaza was the hardest decision we have ever taken. My parents decided to save the last thing that was left, which was “us”. We left in late January 2024 after four months of hardship and witnessing brutal atrocities. Leaving isn’t an option available to everyone. It’s costly and takes a long time. I left behind my beloved family, relatives, friends and neighbours. It felt like my soul had been taken from my body when I received the news that we were leaving. The farewell and our last hugs were so painful, with uncertainty looming over us of whether we would ever see each other again, knowing everyone was at risk of being killed at any moment. The first steps outside Gaza made me feel traumatic shock. A sky without the sound of drones, lights in the streets at night, the feeling of safety where we were staying, knowing that the building wouldn’t be bombed over our heads, charging our phone anytime, having good internet, drinking clean water and food, sleeping in a bed, washing our clothes in the washing machine not manually. These small details have been transformed into distant dreams for every Gazan.

The first months were so hard. My mind couldn’t comprehend what had happened to us, how much the profound loss weighed heavily on our hearts, and how it would be possible for us to live with such emptiness in our souls. It hurts so badly to live with those reoccurring flashbacks of our old life, stuck in the past but hoping that something will happen to bring life and hope to us again. Hearing and reading the news is much more painful, especially since we can’t reach people in Gaza due to the deliberate destruction of the internet and telephone network. We are continually anxious, waiting for a response and fearing that we will see the names of our loved ones on the list of martyrs.

All the people who survived the war share the same pain; we all tell similar stories of our suffering. Wounded people bandage each other’s wounds! I thought that after moving abroad, I could continue pursuing my dreams, only to encounter a harsh reality of exploitation and obstacles placed in our path instead of understanding our circumstances.

GS: You are about to publish your book, Time To Know Palestine. Tell us what this book is about and why you wrote it.

DT: After surviving the war in Gaza, I was trying to recover from the trauma and writing was my way of healing. It was so difficult to turn all the indescribable emotions into words. I was initially unable to concentrate or communicate properly. My family encouraged me to start writing, and I am very grateful to my friend Ana for her unwavering support. She connected me to incredible people from Palestine (West Bank and 48 Lands). They answered all my inquiries and showed me pictures and videos of the places that brought tears to my eyes. It’s so unfair when you can’t visit your homeland while everyone else, including the occupiers, can freely explore its beauty, stroll along its streets and visit all its attractions.

Time To Know Palestine is my way of showing love, pride and respect for Palestine and Palestinians. It’s a message to humanity to see the beauty of my country and know about its long-standing history and vibrant culture. It acknowledges each voice that has been silenced.

This book is for all the lucky people who had or will have the opportunity to live the most beautiful days and memories of their lives in Palestine. And for every Palestinian who is deprived of seeing the beauty of his homeland because of the occupier’s unjust policies.

I will take you on a journey through my words, which I wrote with love and sincerity so that you receive the complete true picture of Palestine, despite all the desperate attempts of the occupier to Judaize and erase its history and geography. This book represents the voice of Palestine that will echo through the centuries, the voice of truth and the voice of the awaited freedom. — Time To Know Palestine

GS: What types of international support for Palestine would you like to see happening at this point?

DT: People worldwide have shown great solidarity for Palestine and its people, starting from the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, which proved its effectiveness. Activism and solidarity campaigns to raise international awareness about the Palestinian issue, the human rights abuses in the occupied Palestinian territories and the victims of the genocide. Grassroots campaigns and protests to support the Palestinian people’s struggle for freedom, justice and equality are growing.

I believe that civil society and social movements play a crucial role in influencing decision-making by applying pressure on governments to implement policies that address the needs and aspirations of everyday people. Many think that providing humanitarian aid and donations to Palestine suffices. However, the real solution lies in tackling the root causes of this ongoing suffering: ending the occupation and halting the genocides.

GS: As one of the places this interview will be published is a zine that will be circulated among young people who like electronic music, I am wondering what types of music you like? What are two of your favourite songs right now?

DT: I like classical music because of its ability to evoke deep emotions and transport me to another world. There is something incredibly calming about the sound of the piano, it helps me unwind and clear my mind. My musical preferences vary depending on my mood and what I’ve been going through recently. Right now, my favourite songs are “I’m Coming Home” by Skylar Grey, and “Gonna Be Okay” by Brent Morgan. They describe the nostalgia I feel for my homeland, my efforts to overcome difficult times and the pursuit of hope.

GS: What are you currently reading?

DT: Most of what I read currently is about dentistry to ensure I don’t forget the knowledge I’ve gained over the past few years and stay updated with new advancements.

GS: What message would you like to send to your generation internationally?

DT: To my generation internationally, I would say: we hold the power to create a more just, compassionate and peaceful world, but it demands collective action, empathy and a genuine willingness to listen and understand each other. In this era of global connectivity, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the obstacles we face, but we must remember that we are also better equipped than ever to make a meaningful impact.

We must advocate for human rights, justice, and equality, recognising that the struggles of one community affect us all. Let’s leverage our platforms, education and resources, not only to improve our own lives but also to stand in solidarity with those enduring oppression and hardship. Let’s actively seek diverse perspectives, build connections, and act with empathy and courage.

Our generation has the potential to transform the narrative — from division to unity and from indifference to proactive compassion. The future hinges on how we engage with the world today and each of us plays a vital role in making it brighter.

GS: Describe what you most admire about Palestine.

DT: At this point in history, what I find most admirable about Palestine is the resilience of its people. Despite enduring decades of hardship, displacement and conflict, Palestinians continue to exhibit remarkable strength and determination. Our capacity to preserve our culture, traditions and sense of identity in the face of adversity is genuinely inspiring.

I am also impressed by the younger generations in Palestine who are actively embracing education, technology and activism to amplify their voices on a global platform. We demonstrate creativity, resourcefulness and a passionate commitment to shaping a brighter future, often employing art, literature, and social media to convey our hopes and challenges.

Furthermore, I have great respect for how Palestinian communities worldwide have managed to maintain their identity, fostering a strong sense of solidarity and pride in our shared heritage, even while in the diaspora. The enduring spirit of perseverance and the continual hope for justice and freedom serve as a powerful testament to the strength of the Palestinian people.

GS: What future do you envisage for Palestine?

DT: The future I wish for Palestine is one where its people enjoy freedom and independence, liberated from the oppression of occupation, living in a secure and culturally and economically prosperous state. I wish for Palestine to reclaim its status as a beacon of knowledge, creativity and peace, just as it was before the onset of occupation.

This interview was conducted in English with Dina Turkeya by Gaele Sobott in September 2024.

Purchase a Copy of Time To Know Palestine

Connect with Dina Turkeya on LinkedIn

Gaele Sobott writing, culture, social & economic justice by Gaele Sobott is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International

10 Questions for Andy Jackson and Gaele Sobott

As a conversation, the poem is inspired by the space between us, the overlap where our concerns resonate and are amplified. It’s shaped most by the insidious nature and continual presence of eugenics in society, and by a desire to find a voice for our agency. We began by deciding to write a double helix, to indicate our collaboration and our genetics—it was a form that both constrained and liberated our phrases.

commutare

I dance. I fly – dog paddle upwards, a vertical take-off like a helicopter (great for escaping danger), and breaststroke through the sky or glide on updrafts. There is joy in the journey. But back down on earth, leaving the reverie, my physical and attitudinal surroundings are not so conducive to travel. I use a mobility scooter or wheelchair to get around and commuting on public transport from Blacktown to Wynyard Station is closer to a nightmare.

To travel to Sydney’s CBD by train, I load my wheelchair into the back of the car using a hoist. It only takes me about ten minutes to drive to the station, then the search for parking begins. There are notoriously few public car parks near Blacktown Station, let alone disability spaces. At Boys Ave there are 130 spots, and eight of those are for disabled commuters. Say I’m lucky enough to find parking. Then I unload my chair, negotiate holes in the footpath, humps, bumps, and kerbs to get to the station. Wait my turn in front of the lift. The doors open and close. It’s overflowing with impatient commuters. I wait a while before the doors open finally to reveal a space for me. I wait for an attendant to let me through the ticket gate. Wait again for rail staff, who are often stressed and grumpy, to organise the ramp to get me over the gap between the platform and onto the train. Over 6000 commuters pass through the Blacktown station turnstiles on a typical workday during morning peak time, 15,800 people during an average 24-hour day.

In a 2019 9News report, Blacktown residents interviewed said they hardly ever get a seat on the train going to or from work. Standing room only, they’re packed like battery hens on the way to the slaughterhouse. Often the train is too crowded for me to board. When I can get on, I need to manoeuvre my way through the crush of bodies and find a place to hold onto a handrail so my chair doesn’t slide when the train brakes. At Wynyard, there’s another wait. The station attendant needs to put a ramp down and help me off the train. Even if a support worker accompanies me, I’m exhausted by the time I get to work and have a raging headache. My joints and muscles scream in pain.

Generally, I avoid public transport, choosing instead to load my scooter into my car and drive calmly through Blacktown’s asbestos jungle. With lockdown, I rarely travelled to the city and now I’m self-isolating, I work from home as much as I can. Today, however, I need to meet with other creatives in person at the start-up hub where our small arts organisation has a desk. The haunting voice of Karen Chilton reverberates through my car. She narrates the story of Sorrowland by Rivers Solomon, the latest book to satisfy my craving for Afrofuturism and Black speculative fiction. Suburban homes flick by, some just starting their gentrification journeys, moving away from the perceived stigma of working-class existence, to maybe one day, achieve the affluent, leafy, suburban bliss of Castle Hill. I glide past Kings Park Industrial Estate, a car and truck rental, and left onto Sunnyholt Road. Turn right, gathering speed, 100 kilometres per hour to merge onto the M7.

Read More

Love

Recorded in collaboration with Speaking Volumes and using excerpts from their anthology, Not Quite Right For Us, we’ll hear ‘The Pilgrimage’ by Amina Atiq; ’Knot’ by Leonie Ross; and ’The Apocrypha of O’ by Gaele Sobott. Our guide is poet, novelist and musician Dr Anthony Joseph.

Listen to the Love podcast here

Celebrating ten years of Speaking Volumes, this anthology is a warning shot, an affirmation, an education

In forty short stories, poems and essays — by turns wry, gentle, furious, humorous, passionate, analytical and elliptical — these forty writers, new and established, speak volumes, invoking their experiences of outsiderness and their defiance against it.

The anthology is available at all good bookshops or on order from Flipped Eye Publishing.

If you enjoyed this episode of NQRFU, try London by Lockdown: a podcast about falling in love with a new city in the middle of a pandemic; remaining curious and open, and making it work. Available on all podcast platforms or our website.

Information

Music composed by Dominique Le Gendre

Narration by Lucy Hannah

Extra music & SFX from Epidemic Sound

Image by Leighann Blackwood on Unsplash

GAELE SOBOTT – DISABILITY, FIRST NATIONS and CLIMATE by Leslie Tate

I interviewed Gaele Sobott, founder and creative director of Outlandish Arts, a disabled-led arts organisation, and author of Colour Me Blue, a collection of short stories set in Botswana, and My Longest Round, the life story of Wiradjuri man and champion boxer Wally Carr.

In the first half of her interview, Gaele introduces her upbringing and disability work, her creative methods as a cross-genre wordsmith and her reaction to the Australian bushfires and the current climate emergency.

Leslie: Could you tell the story, please, of how your interest in various forms of writing and disability arts began, grew and developed? How did your early life shape your creativity?

Gaele: I was born and grew up in regional Victoria, Australia. When I was very young, I did the rounds of all the Sunday schools; Methodist, Anglican, Presbyterian, Catholic, to collect books. I liked the stories. We moved around a fair bit but for as long as I can remember, public libraries were the centre of my world. When we lived in a small fishing town where there was no library, I looked forward to the bookmobile that drove in regularly. My parents also paid off a set of Grolier encyclopedias which provided me with hours of reading. We had an Astor radio with two shortwave bands. I discovered Radio Moscow and would listen to their English program. I received books and plastic records from them in the mail. I particularly loved traditional stories or folktales from around the world about magical and imaginary beings. So I would say that access to stories, books and reading during my early life definitely shaped my later creativity.

My interest in writing developed at school, particularly the secondary school I attended in Melbourne, where I had dedicated English Literature and History teachers who encouraged me to write. I kept a journal during that time and, as a teenager, was influenced by the politics of the Vietnam Moratorium and the growing women’s liberation movement.

I remember seeing demonstrations by disabled people on TV but knew very little about disability politics. I did not then identify as disabled. My understanding of disablement as a political concept only came about in the late 1990s when I began to experience impairment that affected my mobility and my access to buildings, transport and events. My involvement in disability arts only really started in the early 2000s when I came back from living overseas for over twenty years. I met with Amanda Tink and Josie Cavallaro at Accessible Arts NSW, who assisted me quite a lot in understanding the disability arts environment in NSW and Australia. At that time, I started writing my body into my work, the way I moved through the world, my experiences with hospitals and doctors. I was part of the first Australian cohort of Sync, a training program presented by the Australia Council for the Arts that focused on the interplay between leadership and disability. The people I met there and the course itself helped me understand that, as disabled people, we can lead through our art and arts work. I founded Outlandish Arts, a disabled-led arts company for disabled artists across all art forms.

Read More

Astro Turf

by Gaele Sobott

deserts stalk the earth

at ever-increasing kilometers per year

annihilate soil that nurtures new growth

fill the girlchild’s eyes with grit

at ever-increasing kilometers per year

the Gobi the Sahara the Kalahari

fill the girlchild’s eyes with grit

propelled forward like dehydrated race walkers

the Gobi the Sahara the Kalahari

whip up disease-laden dust storms

propelled forward like dehydrated race walkers

valley fever whooping cough meningitis Kawasaki disease …

Read More

I Was Born (Misfit)

Indie Shorts Awards New York Interview with Gaele Sobott

For many disabled people, existence is a continuous act of resistance. I wrote this poem as an act of resistance and because of my growing concern about prenatal screening and diagnosis during pregnancy and Pre-implantation Genetic screening.

Two prominent human rights speakers with Down syndrome, John Franklin Stephens and Charlotte Fien, called on the United Nations to take action against countries that actively aim to eradicate the birth of babies with Down syndrome. Stephens said, “We are the canary in the eugenics coal mine. Genomic research is not going to stop at screening for Down syndrome. We have an opportunity right now to slow down and think about the ethics of deciding that certain humans do not get a chance at life.”

But slowing down is not foreseeable when the prenatal testing market is such an extremely lucrative segment of active growth for the diagnostics industry, estimated to be worth up to US $1.3 billion a year. A report by Fact.MR estimates the global market for Pre-implantation Genetic Testing will reach US $575 million in revenue by the end of 2022. Of course, profit is not the stated motivation for genetic testing. It is sold to prospective parents as a means to eliminating disease, illness and impairment with the expectation of eradicating the existence of various groups of people with genetic mutation. But the critical concepts and protocols involved in deciding who should not be born have not been clearly defined by governments, the medical fraternity, genetic technological corporations or the health insurance industry.

Read More

“For many disabled people, existence is a continuous act of resistance. I wrote this poem as an act of resistance…”

Tweet

Earthly: poems by Gaele Sobott

I allow unarticulated feelings, thoughts and knowing to direct the course of my poems. Floating, allowing the parts of my brain that daydream, intuit, engage in parallel-interactive logic to take over. Maybe, in the end, poetry is a process of interpreting the knowing that exists within bodily experiences, around the body and between one body and other bodies. Surprises and dilemmas emerge along the way and when I work out which direction to take, I spend time crafting a poem.

Some describe elements of my writing as magical. I see these elements as reflections of cultural realities; myth, turns of phrase, musicality of spoken language, the way imagination can be part of the everyday and accepted by a community as such.

I believe my writing is informed by a combination of the joy of imagining, anger, grief, love and disdain. Growing up working class, losing memory, I demand the right to get grammar and other bits and pieces technically wrong, but seek to be subjectively and poetically authentic.

Full article and poems published in Disability Arts Online Showcase

Disability Arts Online is an organisation led by disabled people, set up to advance disability arts and culture through the pages of our journal. Their raison d’être is to support disabled artists, as much as anything by getting the word out about the fantastic art being produced by artists within the sector.

Disability Arts Online give disabled artists a platform to blog and share thoughts and images describing artistic practice, projects and just the daily stuff of finding inspiration to be creative.

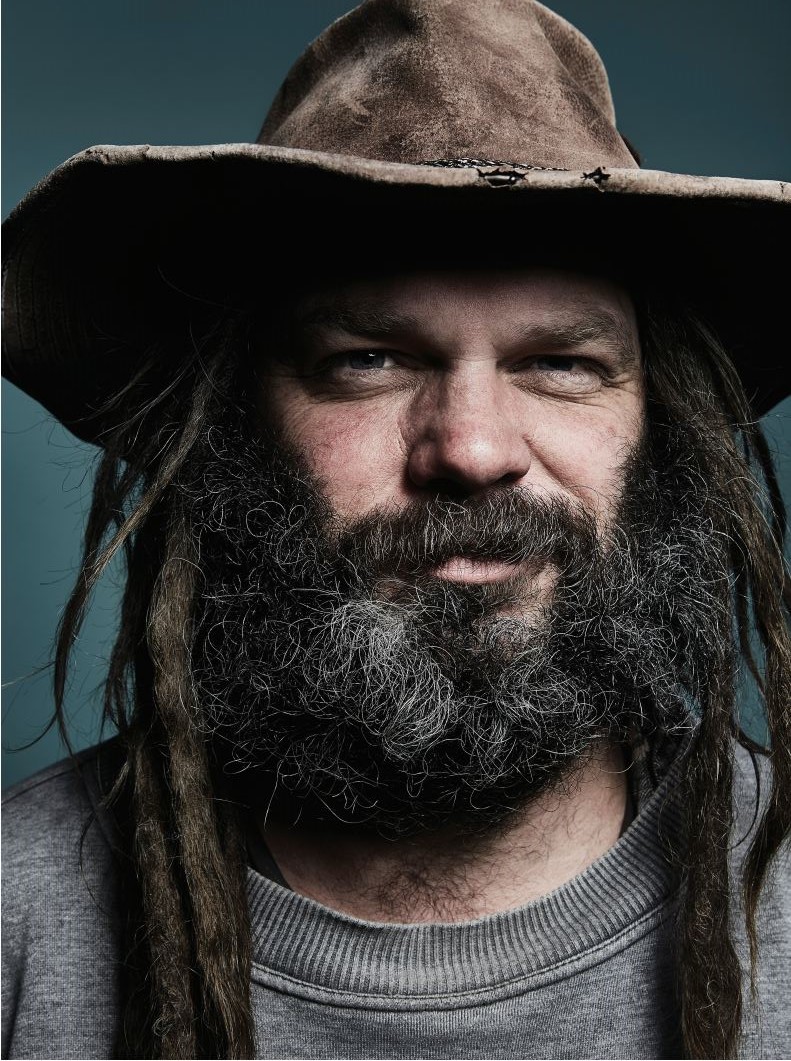

An Interview with Scotty Foster

Now is the time, with climate disaster upon us, to stop concentrating on fighting the boss and make the changes we want to see.

Scotty Foster is a solar powered, radio broadcasting, organic growing, co-operative creating, earth and people-protecting worker from Canberra, Australia. He currently earns a meagre living doing on and off-grid solar and general electrical work. Scotty is creating a co-operative commonwealth, through community groups, and on Community Radio 2XXFM98.3 with the ‘Behind the Lines’ show.

This interview is the fourth of four interviews with volunteers involved in the building of an earthbag water tank at Lucky Stars Sanctuary, Bywong. Vanuatu Earthbag Building assisted in this project. They have provided free plans, support and the materials required to build water tanks for people in need in fire zones in NSW Australia, cyclone zones in Vanuatu and Pacifica.

Gaele Sobott: How did you hear about this earthbag tank building project?

Scotty Foster: I heard through my dad. Someone told the Rural Fire Service that the project was happening. He’s with them, so he passed it on to me in case I was interested.

GS: Does the Rural Fire Service support this type of project?

SF: Yeah, I reckon they would love it. The more places that have tanks next to them specifically for fire protection, the easier their job is.

GS: Was the lack of water a problem in the last fires?

SF: It’s always been a problem around here, yeah.

GS: Why did you decide to get involved?

SF: Well, I can see that it is a simple construction technique that anybody can do. It’s not costly, and all you need is to raise some of your community to come and give a bit of a hand. It’s a very useful method of construction to know about. We’ve got a block out in the bush but we don’t want to be out there in fire season. Given the right conditions, it will go up in flames just like the last fires. We used to go there but now it’s too dangerous. In the previous ten years, fire danger conditions and the ferocity of fires have increased. We now have the new classification of ‘catastrophic’ fire danger. This earthbag technique would be perfect for building a fire shelter that meets the increased fire danger.

GS: How? Tell me more.

SF: The massive, thick walls would hold a lot of heat before transferring it through to the centre of the building. We need that mass in the walls and the sturdiness of the structure. It’s very strong and fireproof.

GS: Do you see other applications for this method of building?

SF: Yeah, it is now almost a year since the last fires began in NSW and there are still a lot of people down the south coast living in tents and caravans. Perhaps this method of building would be useful down there as well and help people to help themselves. If you look back 150 years, communities had building societies, where a bunch of people would get together and pool their resources. They’d then build one house after another after another until everybody had a home. It was a cheap and efficient way for the community to come together, and building codes weren’t such an issue back then.

GS: Are there currently barriers, laws, etc., that make it difficult for communities to go ahead and build as you are suggesting?

SF: Yes, there are many. The Extinction Rebellion mob have come up with a concept called a ‘dilemma action’ where a group of people take some form of action like blocking a road, or in this case building unapproved houses. If the government acts against the group, it will end up looking heavy-handed and idiotic. If they leave the group alone, then it sets a precedent. Building sturdy houses at this time for people who have been forced by fire and lack of government action to live in tents and caravans, is a great moment for that sort of action. I can’t see anything wrong with people getting together and just building their own good-quality houses. The need is huge. If you do it well enough, you can always come back with an engineer who says, ‘Yeah, that’s alright’.

GS: Some politicians are saying as far as climate emergency goes, we just have to adapt. What does adaption mean to you?

SF: Well if we keep putting carbon into the air, there is no adaption. We can’t cope with a climate that is three degrees hotter, let alone six degrees. I don’t know why they are doing this. There is no logic to it. They either deny that climate disasters are happening or they’re like Scott Morrison, who is part of a brand of Christianity which believes in the ‘rapture’, where the world ends and god takes all the true believers to heaven, leaving all the unbelievers to an eternity of hellfire. Of course their church is the only true one. There’s a possibility they believe that it’s time to end the world. Who knows what the motivations of these people are, but they do need to be stopped.

GS: What do you think the alternatives are?

SF: Adaption is one part of survival. Climate change is happening in a significant way, and we are locked into that. They talk about geoengineering. Most of those schemes are extremely risky and pretty crazy but there is one form of geoengineering that would be a really sound way forward. That is to convert the world’s agriculture into organic techniques that take the carbon out of the atmosphere and store it in the soil. We could take all of the world’s agriculture and use it to take carbon out of the atmosphere and to put that carbon back in the soil where it came from. That would go a long way. But we also need to stop damaging our habitat as a way of life.

GS: For this local area and the south coast, what do you think the immediate ways forward are?

SF: We need to change our building techniques for one thing. The way we keep building these crazy English houses here in Australia, particularly with the climate getting way out of control with fire season, bloody pyro cumulus nimbus clouds and firestorms. The earthbag design used to build this water tank protects against fire. Bring it on. Build houses, animal shelters, bunkers. You could build a house by bulldozing up four dam walls in a square, and put a roof on it, if you wanted to. Site it properly of course.

GS: What work do you do? What are you working on at the moment?

SF: I’m an electrician. I have been an organic farmer for many years. I’ve been a blockader and an activist. At the moment I’m building co-operatives to try and create a new economy that will make this crazy one, that is eating the earth and eating people, obsolete. Build an economy that is good for people and good for the planet.

GS: I had the impression that various regulatory hurdles and laws constrained co-operatives in Australia. Is that the case?

SF: It used to be that the co-operative laws were different in every state, which made it quite difficult to trade across state boundaries. That’s been fixed now. The Co-operatives National Law has reduced red tape and simplified financial reporting for smaller co-operatives. I mean you can use any form of governance as long as the registrar lets you do it.

GS: How are your co-ops going?

SF: So far, so good. We’re still in the set-up stage of the community-run farming co-op. We’ve got a renewable energy co-op which has put in one set of solar panels already. It’s called the Pre Power One Renewable Energy Co-operative. It’s designed to enable people who have a roof with a lot of sun shining on it but no money, access to solar energy. It also allows people in the area who would like to take their money out of fossil fuels and put it into something that is reasonably ethical, to do so.

GS: How does the investment bring a return?

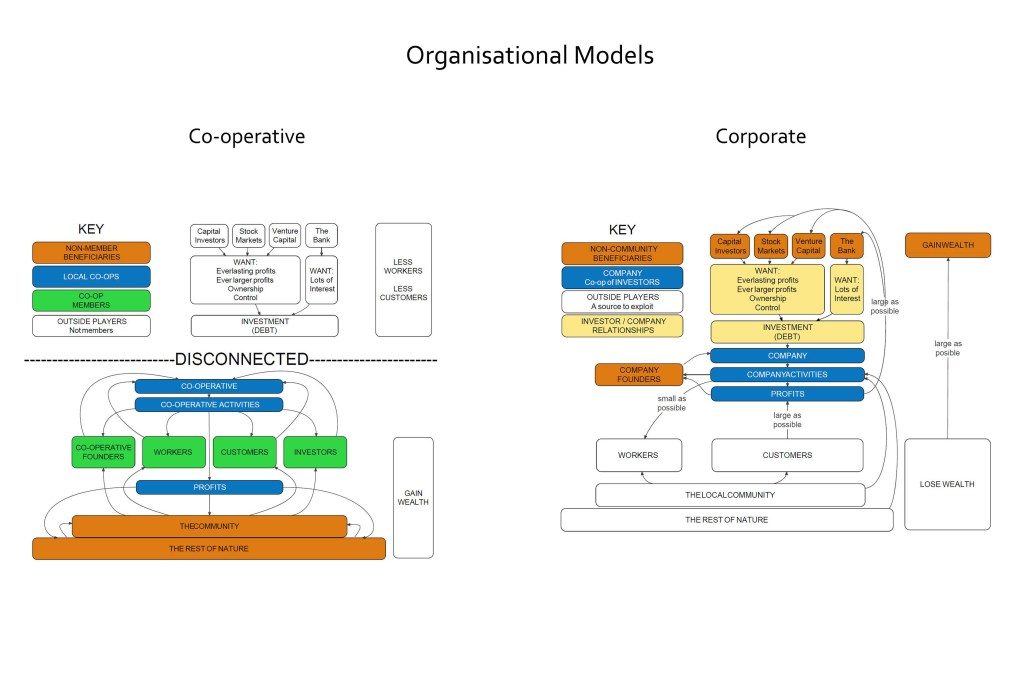

SF: So the way it works is that when you become a member of the co-operative, you get the right to do one of two things or both. If you have a roof that you would like the co-op to install solar equipment on, then you can put up your hand and ask for that. We will come around and make sure your house is suitable, for example, check that there is not a great big blue gum on the north side or something basic like that. If it’s good to go, then we will get a couple of quotes. Then we open up an investment opportunity for the other members who can choose to invest. We get the equipment installed for that member. That gets paid back to the investor when people pay their bills. A portion of that bill will go straight to the investor, and another portion will go to the co-op. The investor will double their money over about twenty years which is a lot better than super. It’s different from perpetual investment which is what most companies offer where if you invest once, you get the right to profits from that company forever. In our case, we prearrange precisely how much we will pay you back. We pay that amount, and the deal is done. You can invest again if you like. The beauty is that all the equipment winds up under the ownership of the people who are using it. That is a major problem in our society. Almost all the productive assets are owned by people who are either extremely rich or completely imaginary, i.e. a corporation. The purpose of corporate ownership is to extract as much wealth out of the community as possible.

GS: How do you maintain the solar units?

SF: There are two ways. You can either put a surcharge, a couple of cents on each payment. As hundreds of people are paying regular bills, we will have a pool of money that we can dip into. Or we can just raise another investment opportunity when the time arises that we need to buy something.

GS: How do you manage the co-operative?

SF: Management is critical. Currently in our society, management is almost always a very top-down, hierarchical, do-as-I-say model. We reckon that it is one of the leading causes of a lot of problems, certainly a lot of mental health problems. If we’re spending a large part of our time at a workplace where we have no control over our work situation, it’s going to affect us. We go through school under that model, and we leave school and face that model again in the workplace. Our families are that model because our parents were taught that model, and their parents too. So how do we do it differently? Luckily, people have been thinking about this for quite a while. We didn’t have to come up with an answer by ourselves. The intentional communities movement uses the sociocracy method of governance and decision making.

This is a system whereby the people who are involved in the community make the rules. The organisational units in the group are “circles” of people who have a defined way of meeting. A lot of the political and power problems that arise in groups these days are from a lack of structure in decision making. There is a lack of knowledge about how the organisation works. So, what happens is the members of the group have to make it up as they go along. Of course, the people who are very forceful and perhaps manipulative tend to rise to the top of that sort of organisation. Sociocracy and holacracy, which I’ll talk about later, are both flatter forms of organisation than the usual hierarchical forms of decision making we find in our society. Meetings are very structured and use a form of decision making called consent which is quite different from consensus. Consensus is where you all need to agree on something before it can go ahead. It can take a lot of negotiation. It is easily stalled by someone who is bent on getting their own way and doesn’t care about anybody else. It’s good for certain things. If people want to form the purpose of their organisation. Then it might be important to use consensus, so everybody is on the same page. Consent is slightly different. A proposal is put forward, and members ask themselves if it is good enough for now and if it is safe enough to try. It is an iterative process. If there are no objections, then the proposal can go ahead. If there is some doubt, the group can say, well let’s try it and come back to assess in a week or six months or a year.

GS: Are there cases where the iterative process should be applied regularly, anyway?

SF: Many of the newer organisational models that have come out of the tech revolution use iteration frequently. Lean methodology is an example of that type of management, but I’m not really up on that. I believe they use iteration a lot.

GS: I imagine it allows for more experimentation, but also it would assist with transparency and accountability.

SF: Absolutely. Our current organisational models do not make transparency and accountability a priority. Transparency and accountability are crucial to creating more humanised ways of organising where people are comfortable and in control.

GS: You said you are also starting up a community-owned farming co-operative. What management model are you applying to that group?

SF: We will be using holacracy which evolved from sociocracy. Sociocracy is an effective form of self-management in situations where there is a community of people living together, like housing co-operatives and other intentional communities. Holacracy is more structured and business-focused. It uses documentation and software, so it’s clear to everybody what the organisation is about. A new member can join the organisation, look up the website and know exactly what the group is about.

GS: Did you establish the purpose of the co-operatives before starting?

SF: We’ve tried both ways now. I came into the Pre power co-op as a bit of a ring-in. It was after the business people involved couldn’t get the concept of a co-op not being for-profit and needing to be controlled by the community. They graciously dipped their lids and bowed out, but then they needed to find someone else to be on the board, who was more aligned with the ideas we are now putting into practice. So, I wound up taking the position. We did have a few things to sort out like a purpose that really fits the bill. There are four of us involved and a couple of other people who come in and out, so it’s taking some time. There’s a lot of work to do in setting up a business.

GS: How do you protect yourselves from burn out?

SF: We make sure that if it is too much to do, we do it next week. We don’t pressure each other with timelines or anything but burn out is a real issue. Part of the model is to ensure that the structure will be easily replicable, so it will be easy for other co-ops to join in. A co-op is a business, and running a business is a pain in the arse and running a business as a volunteer after work is just ridiculous. It’s draining, especially if you’re working long hours. So the model we are working with envisages lots of local co-ops. Pre Power One is the first local co-op we’ve set up, and twenty per cent of the revenue from this co-op will go straight up to what we call Pre Power Central. That is a co-op that is owned by all of the local co-ops. Its sole job is to make life easy for the local co-ops. The central co-op will employ people with that twenty per cent of the revenue, whose job it is to assist with running a local co-op. They will be mentoring. There will be templates for co-op policies, insurance, arrangements with installers, basically all of the hard stuff. It makes it easier for a local co-op to set itself up. All that is left for the local co-ops to do is to hold a certain amount of board meetings per year, run the AGM and figure out what to do with the profits they make.

GS: Are the local co-ops volunteer-run? Are they able to pay themselves?

SF: The locals are basically volunteer run. We use twenty percent of a local co-op’s revenue to pay the central co-op to do most of the work. If a local decides that it needs to pay someone to do something the central coop is not doing, they can do that by agreement amongst the members. The effect would be that the extra wages bill would come out of the discounts received by the members of that particular local co-op.

GS: Earlier you asked, how we organise in a different way when all we know in our families, schools, businesses, government is top-down decision making with little transparency and less and less accountability. How do you think we can start organising differently?

SF: Well, sociocracy and holacracy is one aspect, but it is a huge task to change the existing systems and culture. Sociocracy has been successfully used in family situations before, but we are also going to have to start implementing these processes through education by opening up schools. How we fund those is going to be interesting.

GS: How do you see that happening on the ground say in this area?

SF: I see it as a later stage. The first stage we open co-ops like the renewable energy and the farming co-ops, where the people involved pay their bills. People already pay bills. We are encouraging them to stop paying bills to outside entities that make a profit from them. We want them to start paying bills to an organisation that is owned by them and controlled by them. A form of organisation where they get to decide how to spend any profit in a way which will benefit the community.

We are using a participatory budgeting scheme to distribute our profits. That’s where you have a pool of profits made by the organisation, and the members get to vote and decide how that money is spent. We will have a set of criteria for applicants to pass, and members can vote according to how much they want to give to who. For example, some of those profits could go to building and staffing a school, and some to say, elder care. These are services that are not suited to privatisation or to purely profit-making concerns.

GS: If as a community, you are taking on the responsibility of care and education of your members, does that mean you assume that the responsibility for these services does not lie at a state or national level, or do you envisage starting locally in order to make changes at state or federal government level?

SF: I guess the structure of responsibility that we want to build here is called subsidiarity. It means that decisions are made at the smallest possible level, so if your school can make a decision, that’s great, that’s where it should be made. Suppose there is a circle for cleaning within the sociocratic or holacratic structure of the school, and a decision needs to be made about cleaning. In that case, the cleaning circle should make the decision. If there is a kitchen circle, that is who should make decisions about the food. If you have a complaint about the food, go and see the kitchen circle. From there, you work outwards in a federal manner. You make formal arrangements with other entities that are doing the same thing, so with other schools. Anything that needs doing at a broader level like negotiating with the government or raising funds for particular projects can be done by all those schools agreeing to work together. This method or organising has been successful in northern Syria with democratic confederalism in the Kurdish areas. They spent seven years running a system that was working in exactly that way.

GS: I imagine it takes a fair bit of time to build the structures and culture required to run a system like that effectively.

SF: Major changes like this can really only happen where there is a power vacuum. For example, when Assad deployed all his troops to the south of the country to fight the Arab Spring. The Kurds, who have been fighting Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria, were well-armed and ready to build alternatives. They’ve been preparing for this for a very long time. Abdullah Öcalan has been around for a long time. He was one of the founders of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 1978. The party was not aligned with Russia when it started, and it didn’t take the official communist line as gospel. Because of this they were shunned by the communist world. They evolved towards democratic confederalism. In their guerrilla camps, they’d have a yarn around the campfire analysing how oppression arose historically and decided the first instance of oppression is probably the oppression of women by men. Gender equality is central to their organisational principles. The Kurds are known for their women’s army, which is also democratically run.

Sovereignty is held at the neighbourhood level. That is the ability to make and enforce rules. Within each neighbourhood, sub-communities are represented. The neighbourhood meetings work on a majority vote basis.

GS: How do you see this type of system dealing with exploitation?

SF: Okay, for example, there’s also a women’s council for each neighbourhood. So when decisions are to be made, the information goes out to a group of women in each sub-community. So, there are parallel structures at work in their social contracts.

GS: And wage exploitation?

SF: Well, the Kurdish example covers a very poor area. Historically, under Assad, it was mainly primary production, a lot of crops but no processing of the crops. It was all exported—the extraction of fossil fuels and that sort of thing. Everything gets taken out and shipped away. They have set up a whole system of co-operatives now to do that work. The local communities are federated. Say you’ve got a town with ten communities in it, they band together to organise water and electricity and all of that through co-ops they create in common.

GS: How do they meet their social needs?

SF: Through neighbourhood meetings, I suppose.

GS: Are you saying there is no need for wages?

SF: Oh, I see. I’m not sure. I haven’t managed to get a source about how the economic system works yet. But they have achieved an enormous amount, very inspiring, much longer-lasting and more peaceful than what the Spanish Civil War achieved. The Kurdish example illustrates to me that the federalist model with local sovereignty is entirely possible. It is a way to create a peaceful, sustainable society out of an absolutely turbulent situation.

GS: Here in Canberra, what do you do about the role of media which generally supports and enforces current power structures?

SF: We run a radio show, Behind the Lines on community radio 2XX and make a podcast called Align in the Sound. That is a three-way podcast between the New Economy Network of Australia (NENA), Behind the Lines and a group called Co-operatives, Commons and Communities Canberra (CoCanberra). So if there is something we want to learn, we do it in a public manner. We record it and leave it as a public record and information source that anybody can look up at any time. What a lot of people lack at this point are ideas. We don’t even know that alternative ways of organising and living exist. Who has heard of sociocracy or holacracy or what’s going on in northern Syria? Almost nobody.

GS: Tell me a bit about the organisations, CoCanberra and NENA you just mentioned.

SF: Every month CoCanberra and NENA Canberra region combine to hold a community information or study group night. For instance, we recently invited the National Health Co-op and a co-op from Sydney, called The Co-operative Life, who do aged-care and disability help. We sat the video conference TV on the couch at the food co-op, everyone else sat around it, and they talked about their models, with Q&A afterwards. One is a worker co-op, and the other is a consumer co-op. We were able to explore how they work and why, and what problems they face. We also do asset-based community development training. The idea here is that the community is an asset. The strengths and passions of the community need to be uncovered and used to build solutions to whatever problems that community is experiencing. When we discover or come up with new ideas, we run a workshop.

The New Economy Network of Australia is an Australia-wide networking organisation of people who are essentially trying to build a new economy. CoCanberra is about starting up co-ops and getting things implemented on the ground. The Pre Power and Community Owned Farming co-ops are projects that CoCanberra is deeply involved in. Radio Behind the Lines does long format interviews with anyone who is trying to make the world a better place.

Buckminster Fuller said, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” That’s what we are all doing.

Of course, we do have to fight the old system as well because it’s very quickly munching its way through the planet. The New Economy Network is a co-operative devoted to building a new economy. They’ve been around since 2016 when a conference was held in Sydney by the University of New South Wales law school and the Australian Earth Laws Alliance. At that point, there was no peak body in Australia, so they decided to form one. You can become a member of NENA. It’s got a really good website. They have geographic hubs, and they also have sectoral hubs like an education hub, a First Nations economics hub, housing, food, you name it. There’s a long list. You might live in a regional area, and you’ve got a passion or in-depth knowledge of renewable energy; you can hook up with people from around Australia who have similar values and skills. Behind the Lines is a community radio show that has been going for thirty-two years. I’ve been doing it for fifteen years. We work together with CoCanberra, and have recorded a lot of the New Economy Network conferences. If it’s appropriate to record the CoCanberra / NENA meetups, we will record them. We run editing training workshops over the web, building a team to polish up all that raw audio. Once we finally get them edited, We put them all up as podcasts.

GS: Do you work with unions?

SF: We’ve been trying to, but we haven’t had the numbers to form what they call a union co-op yet. There is interest in Canberra, and there’s a mob in Melbourne called the Earthworker Co-op. They bring together trade unionists, environmentalists, small business people and others in common cause. They began as a coalition of what was left of the Builders Labourers Federation after they got banned, alongside parts of the Green movement. Earthworker operates parallel to us trying to create a co-operative commonwealth on the ground. We are moving towards meeting our needs and capturing the profits rather than letting them go up to all the crazies who currently run the world.

GS: What are the main problems you see with trade unions in Australia.

SF: I think their principal problem is that they are stuck fighting the boss rather than working to make the boss obsolete. They are stuck in a perpetual fight, and that’s not good for culture, spirit or anything else. From being in the system, you become like that system no matter what principles and community support you start with.

GS: What is the main message you would like to pass on to people?

SF: We cannot afford to muck around with slow change any more. Now is the time, with climate disaster upon us, to stop concentrating on fighting the boss and make the changes we want to see by ourselves. We cannot wait for big capital to do it or for the government to do it. We have to do it ourselves; otherwise, it’s just not going to happen. We only have a few years, so we better figure out new ways of organising ourselves to displace the system that is currently ruining the world. Care for people, care for the earth. We can create economic systems that support socially just and ecologically sustainable communities. We can do it, but we have to act now to get it done in time.

Interview conducted with Scotty Foster by Gaele Sobott at Lucky Star Sanctuary, Bywong, 11 October 2020.

Links:

Interview 1 in the series: Kerrie Carroll

Interview 2 in the series: Helen Schloss